IRB 1, 1968, photography [MCA]

IR. PLNS. 0044. 7714. 7554. 7744, 1969, photograph, collage

PLN 8, 1969, photography [MCA]

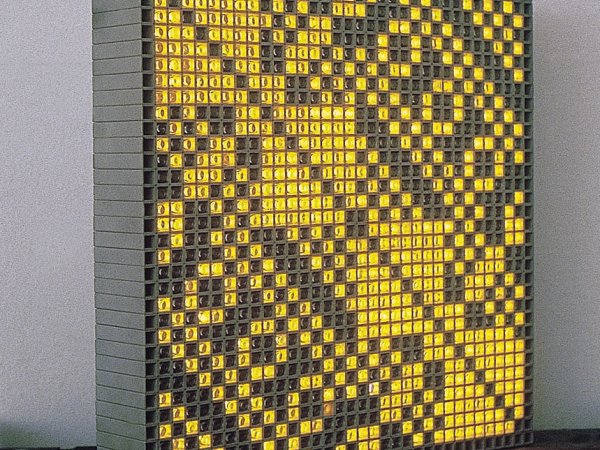

GFE 32 S, 1969-1970, electronic object, 68 x 68 x 12 cm [BCD]

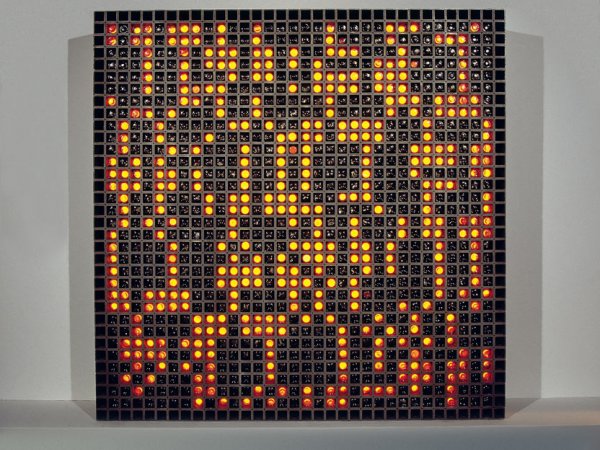

GF 16 NS, 1969-1970, electronic object, 36 x 36 x 12 cm [BCD]

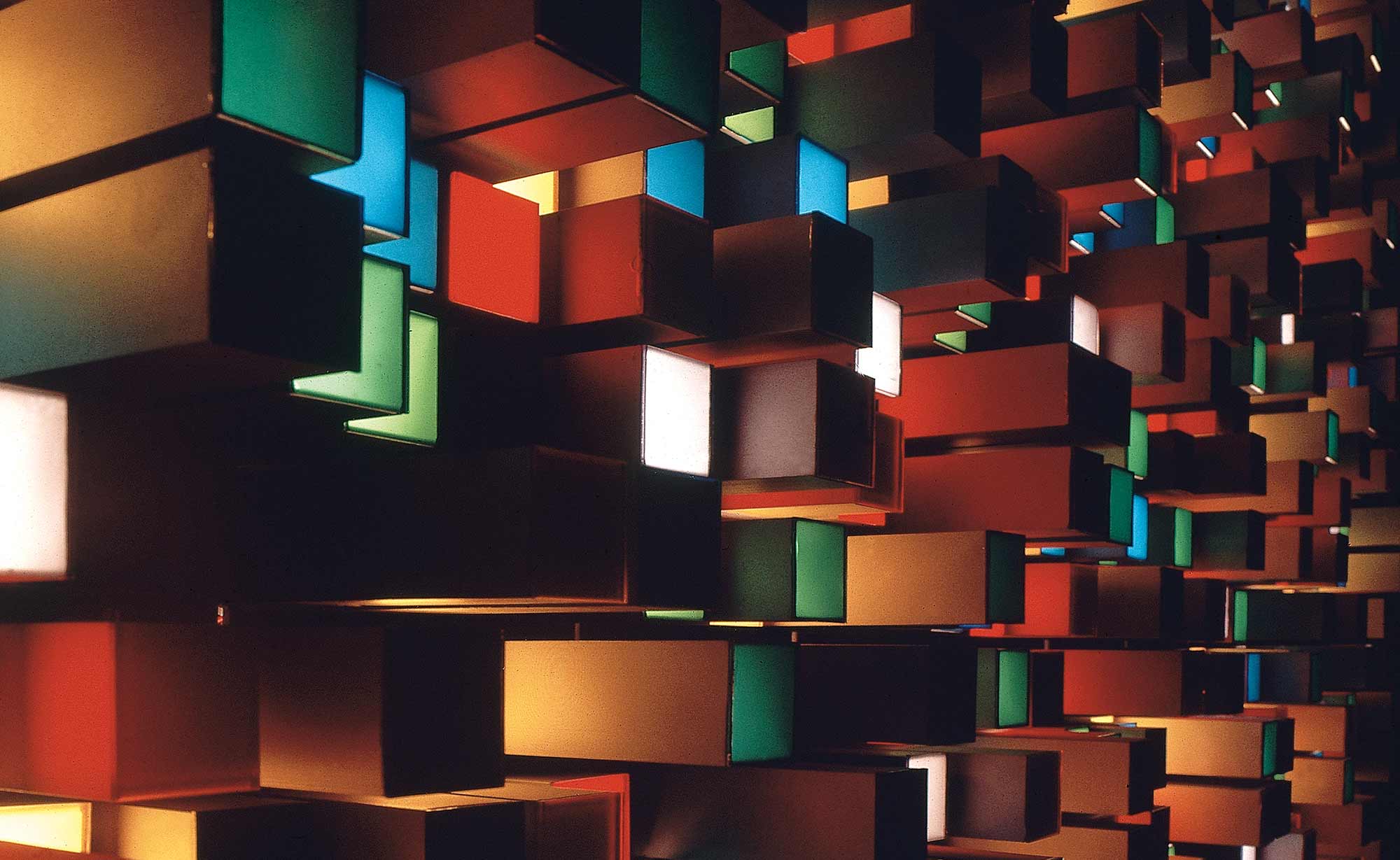

DIN. GF100, 1969, interactive electronic object, 135 x 152,5 x 25 cm, and other electronic objects of Vladimir Bonačić at the exhibition bit international [New] tendencies. Computer und visuelle Forschung Zagreb 1961-1973, Neue Galerie, Graz, 2007 [DF]

Author interacting with object GF. E(16.4) NS C M, SC Gallery, Zagreb, 1969.

GF. E(16.4) NS C M, 1969. - 1974., interaktivni elekronski objekt, detail [BCD]

DIN. PR 18, 1969, light installation, Nama, Kvaternikov trg, Zagreb, 18 x (48 x 88 x 25 cm)

DIN. PR 16, 1971, light installation, Nama, Kvaternikov trg, Zagreb, 48 x (48 × 88 × 25 cm)

DIN. PR 10, 1971, light installation, Nama, Ilica Street, Zagreb, 100 x (88 × 48 × 25 cm) [PD]

Untitled, 1971, light installation, Kreditna banka, Trg bana Jelačića, Zagreb

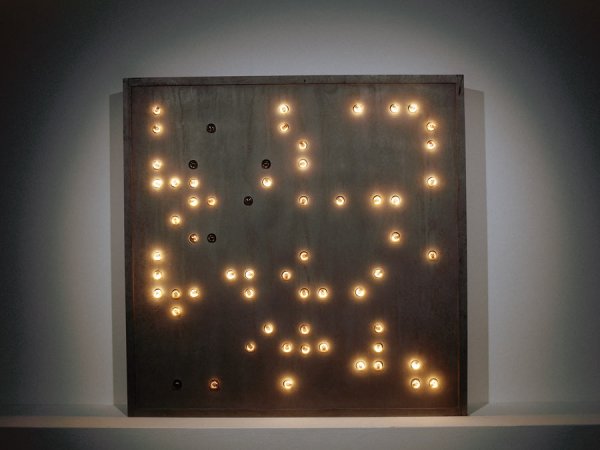

Random 63, 1969, electronic object, 76 × 76 × 7 cm

Vladimir Bonačić (1938-1999) worked in the Ruđer Bošković Research Institute (IRB) in Zagreb from 1964, from 1969 to 1973 being head of the Cybernetics Laboratory. In 1970 he earned a doctorate with a dissertation on the theme of identification of the patterns and structures of hidden data.1 His artistic career started in 1969, prompted by the curators of the Gallery of Contemporary Art in Zagreb, organisers of the exhibition tendencies 4, who championed his being included in art and presented his artworks for a number of years.2 In just a few years, from 1969 to 1971, Bonačić produced a wide range of artworks, while at the same time elaborating them in theoretical terms. After 1971 he worked in the context of the bcd-cybernetic art team, members of which, with him, were the programmer Miroljub Cimerman and his wife, the architect Dunja Donassy. Bonačić was the most prominent member of the group and would sometimes present the work of the group under his own name.

At his first public appearance as artist, at the event tendencies 4 (1968-1969), in addition to the work he produced with Ivan Picelj, the electronic object t4,3 he presented in the gallery premises 21 artworks, and put on in public space his light installation DIN PR 18. Bonačić took an active part in all programmes of the event tendencies 4 under (the identical) titles computers and visual research, at a colloquium of 1968 and a symposium of 1969 with presentations the texts of which were published in the journal bit international while at the 1969 exhibition he won a prize. The panel of judges liked "the harmony between the mathematical results of the programming and the visualisation of the processes that stemmed from the programming. We particularly commend Bonačić's new approach, which includes solving the problem by taking image and not number as parameter, thus opening up the possibility of resolving much more complex problems."4

Pseudo Random Numbers of the Galois Field

Galois fields, named after the French mathematician Évariste Galois (1811-1832) were for Bonačić an inexhaustible source of information in both scientific and artistic work. In abstract algebra, finite fields are known as Galois fields; Bonačić studied them in connection with his work on the roots of polynomial equations. Galois developed a theory in which field theory (a more complex system) is connected with group theory (a simpler system), He showed "by analysis of analysis" that the solution of the insoluble can be achieved outside the known -- in the unknown -- if we enable, by changing our thinking and behaving, a new approach to the process of cognition.5 At first in his scientific work and then in his artistic, Bonačić developed his own original method of studying Galois fields by visualising them: "One of the most interesting aspects of this work is the demonstration of different visual phenomena of patterns that derive from the polynomial, which mathematicians who studied Galois fields earlier did not record."6

At the first exhibition that was part of tendencies 4 in 1968, he exhibited eight computer-generated images entitled from IRB 1-9 to IRB 8-9, IRB standing for the Ruđer Bošković Institute in which the works were produced, and the numbers were just labels for identifying the exhibits. All the works on exhibition were photographic reproductions of various formats of shots of "Screen with luminous pen", a graphic system that Bonačić devised and constructed with a creative combination of existing hardware.7 The screen was connected to the computer PDP-8. The programme language Assembler was used for the programming. With the use of the luminous pen an original graphic interface was established (visually more intuitive as well) for controlling the computer via the screen similar to the technology of today's light pen.8

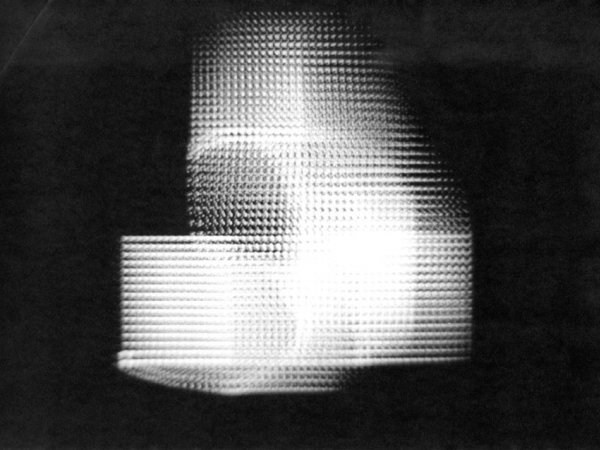

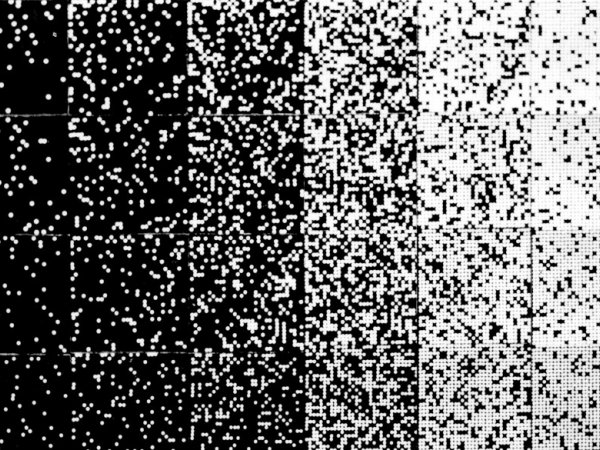

In a series of ten photographic works with the label PLN of 1969, numerical combinations were visualised in fields (grids) of 16 x 16, 32 x 32 and 64 x 64 elements. Five of the works contain in their name an exact description of the algebra that the image visually presents, for example, IR. PLNS. 044. 7714, 7744, in which IR denotes the irreducible (indivisible), PLN the polynomial, S symmetry and the numbers give the pertaining characteristics of the polynomial. In all five works the photographs show a sharp image of points registered on the screen of the oscilloscope. Because of the then technologically restricted number of depictions of fields on the screen, some works were done by joining together several photographs, a greater "resolution" thus being achieved, i.e., an enlarged number of elements depicted. IR. PLNS. 0044. 7714. 7554. 7744 is composed of 28 screen shots, in greater resolution accordingly at the same time seeing the "behaviour" of the various degrees of the algebra visualised. The subsequent five works do not contain numerical designations of the polynomials used, but are presented with the title PLN to which designations from 5 to 9 are added.9 They do not depict the sharp contours of the dots of the "frozen" image on the screen. In this series there is no collaging of photographs and only one photograph of the whole screen of the oscilloscope is produced. The works PLN -- 5 to 9 resemble experiments with photographic focus and exposure, but are actually obtained by creative use of the parameters of the hardware and the software, a new dimension in the depiction of static elements and their spatial relations being achieved. The works PLN -- 5, 6, 7 and 9 resemble a long exposure photographic image, in which the elements depicted no longer have sharp outlines. Precisely because of the technical peculiarities of these works, Bonačić collaborated with photographer Marija Braut, who was then photographic assistant at the Gallery of Contemporary Art.

Dynamic objects

Bonačić elaborated the time dimension, accomplished through the combination of the technology of computer-generated image and photographic medium in the works mentioned, in a series of digital luminous and audiovisual objects that he called "dynamic objects". These were in a sense sculptural screens that also contained the performative, temporal dimension. They created and performed rhythmical images of Galois fields. These works opened up the possibility for interaction with observer/user. Interaction was on the whole enabled on the temporal axis of the sequence of images depicted: initiating, halting/pausing, changing the rhythm, looping a selected sequence.

From 1969 to 1971, Bonačić created a series of dynamic objects consisting of various digitally programmed light patterns visualised on specially designed screens made of metal tubes of different shapes and sizes. For all his dynamic objects, Bonačić made use of the "pseudo random" algebra of the Galois field (GF in the title of the work) and they were programmed on the SDS 930 computer in Real-Time FORTRAN enabling the direct use of Assembler, with which the individual bits were easier manipulated. The programmer of all the dynamic objects was Miroljub Cimerman, a colleague from Ruđer Bošković. Bonačić used customised hardware for all his dynamic objects, which experts at the IRB either produced themselves, or else assembled. They were embodied statements of what he later worked out in his critiques of the influence of commercially available equipment on digital art, the use of which he wrote would be "like an artist limited to the use of just two or three colours in a picture. It is true that with this kind of equipment much can be done, but we can hope that ways for a better use of the computer will be found."10 Bonačić explained that the dynamic object was "sculpture and concept in art in which an indissoluble unity between computer system and work of art was established"11 while in a different piece of writing he went on: "Integration of computer systems and art, not allowing one to dominate the other, is considered a step forward in the direction of a common language. That means that the artist and his artwork are capable of communicating; artists and their art use a common language."12

The dynamic object GF. E 32-S (1969-1970) generates successive elements of the Galois field at the greatest distance from each other and shows them as symmetrical patterns with synchronous selective flashing on the front plate of the object. The object is like a screen made of a network of 32 x 32 square aluminium tubes that contain bulbs. The total screen resolution comprises 1024 monochrome "pixels". The generator of the Galois field is part of the purpose-made computer placed within the object, which enables it to operate on its own, without any external computer. Control of the rhythm of the visual patterns made is modifiable and interactive on the part of the observer, who can adjust it to between 0.1 second and 5 seconds. In a two-second rhythm, the same pattern will be repeated in about 274 years. On the rear of the object the observer will find "manual controls for initiating, stopping, speed control and choice or display of any pattern at all. With binary notation, 32 indicator lights and 32 keys it enables any pattern from the array to be set or read."13

Bonačić's dynamic objects were pioneering examples of interactive digital art at a global level. Like many other artworks in the context of the NT,14 Bonačić's dynamic objects were also devised as artworks that could be experienced aesthetically, as well as instruments for visual research. In particular, the latter aspect could lead us to the cognitive process (visual learning of mathematics and its hidden laws), which Bonačić actually mentioned describing his artistic production.15 Such experimentation and visual research (in the literal sense of the words) could be performed in the controlled setting of an art/science studio/laboratory with the assistance of the artist, or could be entrusted to the general public in a gallery, for independent control.

The front plate of the dynamic object DIN. GF 100 (1969) is made of a matrix of 16 x 16 light elements in 16 different colours, each one of which appears 16 times. With the use of a Galois field generator, DIN GF 100 can produce 65,535 different images or patterns.16 Depending on the decision of the user or observer, the picture will change at a rate of from every 200 milliseconds to 2 seconds, taking the observer into the pseudo-random procedure. The object can be set to a self-start mode or an interactive manner of work, when it is exhibited with a remote controller, as it was in 1969 at the exhibition tendencies 4. The observer can control the light patterns via a control board at the back of the object or with a remote controller linked by a four-metre-long wire with the object, meaning it was far enough away for interactive observation from a distance. Clicking the buttons of the control enabled manipulation of the speed of the sequence and examination of the pictures of the sequence step by step, similar to looking at a film frame by frame.17 This film was not abstract, showing very concrete visualisations of Galois fields.

Bonačić incorporated a higher level of interaction into the dynamic object GF. E(16.4), devised, developed and built in Zagreb between 1969 and 1971. The dimensions of the object were 187 x 187 x 30 cm, and it weighed half a ton. The front panel (screen) had a relief structure, made of 1024 fields in 16 colours. Three Galois field generators lit up this three-dimensional screen, creating various patterns and controlled the sound that came from four speakers. The researcher/user could affect the picture and sound manually with the use of dozens of different buttons and switches on the computer compiled for the occasion that was alongside the object. The sound can be manipulated by dropping out individual tones. The tempo of the visual can also be adjusted and selected sequences can be looped at will. But the observer cannot change the logic of the system. The whole composition of this audio-visual spectacle, which consists of 1,038,576 different visual patterns and 65 sound oscillators can last, depending on the rhythm chosen, from 6 seconds to 24 days.18

Artistic installations in public space

Bonačić also developed digital light installations for public space that enabled a different kind of interaction, at a social level. As part of the event tendencies 4, in 1969, on the façade of the Nama department store, opened just a year earlier, on Kvaternik Square in Zagreb, a 36-metre digital light installation was put in place, the DIN.PR 18. It consisted of elements, each done in a grid of 5 x 3 luminous elements. The installation put on a light show flashing geometrical patterns of the algebra of the indivisible polynomial of degree 18 (in a feedback x18 + x5 + x2 + x + 1) In all 262, 143 images were successively shown in a variable rhythm. The fastest tempo in which the image could be changed was 200 milliseconds, and it was possible to adjust speeds to the limits of observer perception and rhythm.19 There is no information about what rhythm the work was presented at or whether the installation was constantly lit up in the same rhythm or was changed. At that time Kvaternik Square was poorly lit, and so the installation worked as a kind of additional street lighting. Fedor Kritovac analysed the context of the urban lighting of Zagreb, placing it in a broad range from tasteless ads for household products to the broken bulbs of the street lighting. "Do we consider the random event or a pseudo random event an irresponsible light column, a message?"20 In what is otherwise a positive analysis of DIN. PR 18 he gives some criticisms of its execution: "the range of the frieze is too broad to be able from the permitted distance to take it all in at once, the intensity of the signal is physiologically uncomfortable for it is too strong in comparison with the surroundings."21 Like Kritovac, art historian Želimir Koščević wrote a critique of the work through the prism of a criticism of consumer society while positively assessing the aesthetic message of this light display, contrasting it to the commercial neon adverts that at that time had just started to appear on the streets of Zagreb. He also emphasised the continuation of the idea of the democratisation of art proclaimed through the NT.22 He observed that Bonačić

with his ideas, is part of the front that within the tendencies movement is endeavouring to pave the way for art that will simply be work, the results of which will be intended for all, without any obligation on us before we are able to come face to face with it to take off our hats and pay an entrance ticket, unavoidable in the museum or gallery.23

The next luminous dynamic object, the name of which we cannot determine, was put up in 1970 on the façade of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade, opened just five years earlier, in 1965.24 The work as exhibited in the context of the 4^th^ Triennial of Yugoslav Art, selected by Ješa Denegri. In the Mladost bookshop in Zagreb, Bonačić put on two works. In 1969 in the façade of the Ilica Street branch he put up the caption SALON MLADOST. The letters were written in an original typography composed of square "pixels". Following the proportions and materials used for the caption, the dynamic object DIN. PR 6 was designed, consisting of two parts, put up by the caption. For New Year 1970, the sculpture New York was put on show in the interior.

In 1971 Bonačić put on as many as three big light installations in Zagreb public space. Reusing the same space, at the top of the façade of the Kvaternik Square Nama store, he put on a somewhat more complex installation, DIN. PR 16 now in a triple frieze of light elements. An additional spatial expansion was made with new light elements placed in a recessed part of the façade. The algebra of the polynomial of degree 10 was rendered in light. In the very centre of the town, some twenty metres down Ilica Street, the next two installations were put up, now on the facades of historic buildings. All along the façade of the Nama branch in Ilica Street nos. 4 to 6 the installation DIN. PR 10 flashed its 100 luminous elements, and is accordingly a forerunner of the media facades of today.25 The ground floor of the building pulled back inside and opened with columns at street level,26 and in height the light installation extended from first floor to the top of the building. Just a hundred metres further off, another installation was put on, its name now unknown, on the façade of Kreditna banka Zagreb (today Zagrebačka banka) on Ban Jelačić Square, the main square in Zagreb. In all eight light panels were arranged on two balconies on the third floor of the neo-Classical building, over the monumental neoclassical columns that reached the balconies.

In 1971 Bonačić worked out a concept for the Project for decorating the façade of Zagreb Tobacco Factory, probably in Klaić Street, but it never came to fruition. It was imagined in three phases of execution. In the first phase, Putting in place a series of 19 objects, the making of dynamic objects that "gave flashes of blue or bluey-green light", which was followed by Putting in place letters and symbols done in aluminium and lit spotlights, and a final part, Tower Set Up, which was "controlled by a computer system and gave out luminous messages at will or a game of light"27 The idea was for the tower to be 8.5 m tall, with a square plan, consisting of aluminium prisms sized 14 x 14 x 30 cm closed with pieces of glass of a certain colour.

In 1971 Ješa Denegri wrote of the luminous dynamic objects and their presentation in public space:

...since their programmes are written with the help of computers and the objects are produced in pure electronic technology, they are not restricted either in their dimensions or in their ambientation, rather, in their approach can be done as sculptural units the operation of which is meant for the spaces of contemporary urban landscapes. From the very beginning of his work, Bonačić has been aware that the innovation he has championed must not stop at the mere technical refinement of objects of the New Tendencies type and function, for, although their work started with the construction of a single object of the chamber format, he does not wish to build aesthetic objects meant for the exhibition business in closed gallery and museum venues but as necessary component of all his works, he postulates the factor of their being integrated into the live urban fabric.28

Not one of the installations in the public is there at the given locations any more in any shape or form, nor are their original components accessible. But it is highly consoling that all of Bonačić's electronic dynamic fragments meant for indoors are available. Because the original objects work today, partially or fully, they belong to an exceptionally small group of digital interactive objects from the sixties that still function and can be shown in their original shape. For this we have to thank the fact that electronic logic was built into the very objects and they do not depend on any specific, today more or less unobtainable, external equipment or obsolescent computer programmes, as is the case with other electronic objects of early digital art. In total eight electronic dynamic objects have been restored with only the original materials and were shown at the exhibition Bit international [New] tendencies und visuelle Forschung Zagreb 1961 - 1973 in the Neue Galerie am Landesmuseum Joanneum in Graz in 2007 and in Medienmuseum pri Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie (ZKM), 2008--2009, selected and curated by Darko Fritz.29

Criticism of the use of the random in digital art

From the series of works IRB that Bonačić presented publicly in 1968, one work that was not shown was labelled IRB 9-9 and showed the contours of a female figure, which, like the later work Random 63 (1969) refers us to the artist's curiosity as well as to an interesting working process with the premises of which the artist personally did not agree, but still produced them for experimental purposes. The computer drawing of the human figure in IRB 9-9 is in opposition to the author's repeatedly and trenchantly emphasised wish to use the computer to create "something that has not been made" and in line with the conviction that "the computer must not be just a means for the simulation of the existing in a new form. There should be no computer painting in the manner of Mondrian or composing in the manner of Beethoven. The computer provides us new contents, reveals a new world to us. In this new world after a number of years scientists and artists will meet once more sharing the desire for knowledge."30

The reference to Mondrian was a criticism of the experiments of A. Michael Noll with computer-generated Mondrian drawing that in a questionnaire Noll had had compared with a reproduction of the original painting.

Bonačić criticised reliance on the aleatory principle in digital art, thinking people simply better "in the creation of an aesthetic programme that suits human beings."31

In 1969 he discussed the concepts of information and entropy, redundancy and originality in the theories of George David Birkhoff, Max Bense and Abraham A. Moles. Alluding to the claim of Moles that redundancy creates structure at the expense of originality, Bonačić writes:

Observing the qualitative relation as aesthetic measure, we arrive at the conclusion that the maximum originality (in other words, the disorder that arises with the random selection of symbols) leads to immeasurable aesthetic values. Let us suppose that we arrived in some different way at a programme that as a result gave an aesthetic object. With the use of random-number-generator we will distribute existing information at random. In the consistent use of a random generator, irrespective of the result of the programme, we talk of maximal originality. The use of a random number generator leads to a random and unrepeatable depiction of the state of affairs, one that has no value for the human being. Information arising in this way can evoke various associations in the observer. But the computer used in this way lags far behind human beings. Even if the expressive capacities of the computer (the realiser, or peripheral unit) were the same as man's the essence of Pollock's world and work would not be surpassed, irrespective of the complexity of tomorrow's computer and peripherals. This does not mean that the human (monkey or some other animal) cannot with the help of the computer create an aesthetically relevant object if he operates, whether awarely or unawarely, submitting to the laws of chance.32

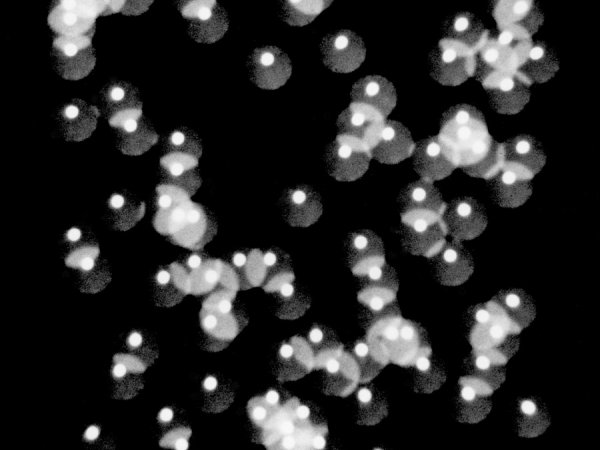

This critique prompted the creation of the object Random 63 [sic], 1969, when 63 independent generators of true random numbers33 were used for a drive of 63 bulbs.34 The geometry of the arrangement of the bulbs on the object was deliberately generated with the use of the pseudo-random Galois field by an exact method. This is the only Vladimir Bonačić work that uses true randomness and can lead us to (only) aesthetic pleasure or irritation.35 All other Bonačić works are founded on pseudo-randomness with the use of Galois field algebra, which is exact and, in principle, enables the visual and auditory comprehension of the laws of maths. Observing these works, open aesthetic processes, the viewer or user can understand what are otherwise invisible and to people unpredictable mathematical (universal) laws. Visual results are expressed as a sequence (sometimes measured with a number of combinations in the millions, depending on the number and power of the polynomials used) of symmetrical or asymmetrical compositions in the given geometrical grid.

At a Zagreb colloquium in 1968, pioneer of digital art Georg Nees said:

Should not information aesthetic be able to use certain modelling techniques? The information it should model is aesthetic information, of the kind that appears in nature and art. But also needing modelling is the process dependency of aesthetic information, in which the process should be understood as temporally dependent information.36

We can find similar ideas in Jonathan Benthall:

Max Bense writes that that mathematical aesthetic is a procedure that is 'devoid of any subjective interpretation and objectively deals with specific elements' of the aesthetic state as, it might be said, specific elements of aesthetic reality. These elements include meaning as well as sensory and formal features. Bense proposes "a generic aesthetic" that would explain how aesthetic states are generated in the same way as generative grammar in linguistics attempts to explain the logical processes in which sentences are derived and explained; but he thinks that a previous phase of analytical aesthetics is required. The main mathematical techniques that Bense proposed are semiotic (study of signs, the source of which is Charles Sanders Peirce, and others) metric (deal with forms, features and structures) statistical (relates to the probability of the occurrence of elements) and topological (relations between sets of elements).37

Benthall continues:

Vladimir Bonačić is sceptical about the applicability of information theory to aesthetics, for it takes semantics so little into consideration. But he approaches visual phenomena in a mathematical and systematic manner.38

With his digital light installations in public space, Bonačić for a short time at least accomplished the utopia that NT had desiderated: the work is exact, science is humanised, art is scientised, the work is produced with the use of machines and by the programming of dedicated software and with the construction of new hardware, it can be multiplied. It is socially active and democratic, even has a use function at the level of street lighting (which was then read as criticism of the consumer society in the context of commercial neon adverts in public space). Bonačić produced a new universal language with his idiosyncratic approach to creative work and the making of artworks that strode across the borders and categories of rational and intuitive, artistic and scientific, aesthetic pleasure and cognitive process. Today's world and the information society would certainly be immensely better if a larger number of people took Bonačić's 1969 words more seriously: "Anyone who works with computers should be a researcher who has to be aware of what they don't know."39

-

Vladimir Bonačić, Pseudo-slučajna transformacija podataka u asocijativnoj analizi kompjuterom, doctoral dissertation, Electrical Engineering Faculty, Zagreb University, 1970. ↩

-

Letter from Boris Kelemen to Jasia Reichardt, September 22, 1968, archives of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb. ↩

-

See the description of the work in the introductory text ↩

-

Other prize-winners were Marc Adrian and the group Compos 68. Members of the panel of judges were Umberto Eco, Karl Gerstner, Vera Horvat Pintarić, Boris Kelemen and Martin Krampen, Kompjuteri i vizualna istraživanja, odluka ocjenjivačkog suda, catalogue of the exhibition tendencies 4, Gallery of Contemporary Art, Zagreb, 1970. ↩

-

Miroslav Cimerman, untitled, PLN, print album, Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb, 2010, n. p. ↩

-

Vladimir Bonačić, \"Kinetic Art: Application of abstract algebra to objects with computer-controlled flashing lights and sound combinations\", Leonardo, vol. 7, Oxford/New York: Pergamon Press, 1974, p. 193 ff. ↩

-

Souček,Čuljat, Bonačić, "Optička komunikacija s \'ON LINE\' računalom pomoću svjetlosnog pera", Automatika, nos. 2-3, 1968., spp. 155-159. See p. 18 ↩

-

"The selection of certain parameters for photographing was carried out interactively via switches and signal registers on the control panel of the PDP-8 computer. Enhancement of the visual impression of the simple technological two-dimensional (x, y) depiction and obtaining the desired artistic impression of the PLN series was achieved with a series of interactive analogue-digital electronic operations (on the actual system screen with light pen, by direct access to the computer programme (at the level of individual bits) and photographic procedures". Miroslav Cimerman, untitled, PLN, graphic album, Museum of Contemporary art, Zagreb, 2010, n. p. ↩

-

The designations of the works in the title are given only for the sake of differentiation. They stem from the order in which they were placed at the exhibition tendencies 4 of 1969. The labels stuck after the exhibition. ↩

-

Vladimir Bonačić, \"Kinetic Art: Application of Abstract Algebra to Objects with Computer Controlled Flashing Lights and Sound Combinations\", Leonardo, vol. 7, no. 3, 1974, p. 253. ↩

-

Vladimir Bonačić, \"On the boundary between science and art\", Impact of Science on Society, vol. 27, no. 1, January/March 1977, p. 25. ↩

-

Vladimir Bonačić, \"A Transcendental Concept for Cybernetic Art in the 21st Century\", Visions for Cybernetic Art, exhibition catalogue, Paris Art Center, Académie Européenne des sciences, des arts et des letters, Paris, 1987, n. p. ↩

-

Vladimir Bonačić, \"Kinetic Art: Application of Abstract Algebra to Objects with Computer Controlled Flashing Lights and Sound Combinations\", Leonardo, vol. 7, no. 3, 1974, p. 255. ↩

-

For example the Reliefometer (1964--1967) of Vjenceslav Richter, the lumino-kinetic works of MID group or Un instrument visuel (1965) of Michel Fadat, all shown at NT exhibitions, ↩

-

Vladimir Bonačić, \"Art as Function of Subject, Cognition and Time\", paper read at the symposium Kompjuteri i vizualna istraživanja, Zagreb, May 5 and 6, 1969., Bit International, no. 7; Dialogue with the Machine, 1971, pp. 129--142. ↩

-

Catalogue of works, Vladimir Bonačić, tendencies 4, 1970, exhibition catalogue, Gallery of Contemporary Art Zagreb, 1970, n.p. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

The object was exhibited at the 7^th^ Paris Biennial in the Interventions section in Parc Floral, Bois de Vincennes, from September 24 to November 1, 1971, curated by Ješa Denegri; in the UNESCO building in Paris from November 1971 to November 1972 marking the 25th anniversary of UNESCO; in the Franciscan Church of St Kilian, 1984, and at the exhibition bit international [New] Tendencies -- Computer and Visual Research (Zagreb 1961-1973), ZKM, Karlsruhe, 2008-2009, curated by Darko Fritz. ↩

-

Vladimir Bonačić, Eksponati u okviru tendencija 4 Zagreb maj 1969, captions for works at the exhibition Tendencies 4, p. 3 and 4, Archives of the MCA, Zagreb. ↩

-

Fedor Kritovac, \"Generator slučaja i svjetla velegrada\", Vjesnik, no. 8069, August 5, 1969, p. 8. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Želimir Koščević, \"Svjetlost nove urbane kulture\", Telegram, no. 479, July 4, 1969, p. 17. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

A Modernist building built to a design of Ivan Antić and Ivanka Raspopović of 1960. ↩

-

Darko Fritz, \"Media Façades and Urban Media Environments -- Developments of Art Practices\", What Urban Media Art Can Do, ed. Susa Pop, Tanya Toft, Nerea Calvillo, Mark Wright, in association with Connecting Cities partners, AV edition, Berlin, 2016, pp. 414--423. ↩

-

The remodelling of the façade by the joining of buildings at numbers 4 and 6 was done after a design of Stjepan Planić of 1937. ↩

-

Vladimir Bonačić, Projekt uređenja fasade tvornice Tvornica duhana Zagreb, n. p., Archives of the bcd -- cybernetic art team. ↩

-

Ješa Denegri, \"Uz vizuelna istraživanja Vladimira Bonačića\", Život umjetnosti, no. 14, Matica hrvatska, Zagreb, 1971, p. 50. ↩

-

In 2006 Miroljub Cimerman, Marija Gattin, Darko Fritz and Museum of Contemporary Art technicians renovated DIN. GF 100 and put in order the remote controller that enabled interaction with the work in Neue Galerie, the first time after 1969. Miroljub Cimerman, Dunja Donassy and ZKM technicians in 2007 renovated GF. E / 16,4 for its first public showing after 1985. ↩

-

Vladimir Bonačić, address at computers and visual research, May 6, 1969, Zagreb; audio archives of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb. The quotation is to be found in the publication: Vladimir Bonačić, \"Arts as function of subject, cognition and time\", address at the symposium computers and visual research, May 5 and 6, 1969, Zagreb; published in bit international, no. 7; Dialogue with the machine, Gallery of Contemporary Art, Zagreb, 1971, pp. 129--142. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

For generator of random numbers fluorescent bimetal starters were used. ↩

-

Bulb specification: E14, tube shaped, 220 V, 10 W. ↩

-

The use of pseudo-randomicity in the control of the lower part of the electronic object t4 of 1969 has not been ascertained. ↩

-

Georg Ness, \"Computergraphik und visuelle Komplexizität\", bit international, no. 2, 1968, City of Zagreb Galleries, p. 32. ↩

-

Jonathan Benthall, Science and Technology in Art Today, Thames and Hudson, London, 1972., p. 59. ↩

-

Ibid., p. 62. ↩

-

Ibid., as 29. ↩