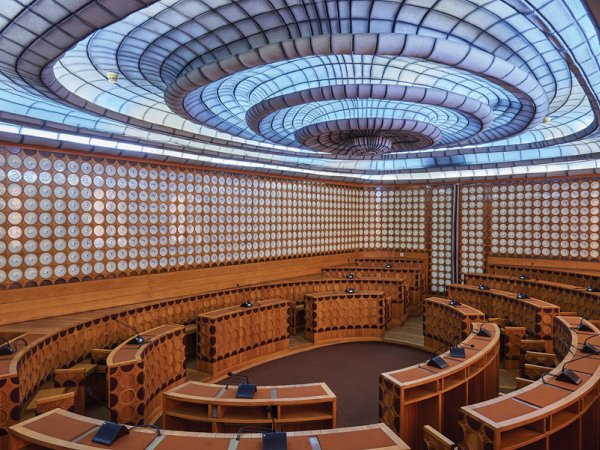

Economic Council, Old City Town Hall, Zagreb, 1958-1971, situation in 2020 [SK]

Economic Council, Old City Town Hall, Zagreb, 1958-1971, situation in 2020 [SK]

Culture and Education Council, Old City Town Hall, Zagreb, 1968-1971, situation in 2020 [SK]

Culture and Education Council, Old City Town Hall, Zagreb, 1968-1971, situation in 2020 [SK]

Culture and Education Council, Old City Town Hall, Zagreb, 1968-1971, situation in 2020 [SK]

Culture and Education Council, Old City Town Hall, Zagreb, 1968-1971, situation in 2020 [SK]

Wedding Halls, Old City Town Hall, Zagreb, 1973, situation in 2020 [DF]

Wedding Halls, design for door leaf, 1973

The contemporary house is easier to create. But beforehand, a lot of effort has to be put in – to forget everything that is and start with two little truths Man.

Machine.

Man – a being with a wish for joy in life.

Machine – a means that serves man in the accomplishment of this lifetime goal.1

With these words, architect and architectural theorist Andrija Mutnjaković (1929) starts the description of his Domobil project2 (1964), for a residential building with a moveable roof that opens up like a flower. Unfortunately, the house was never built, either in the Hollywood it was designed for or anywhere else, although the author proposed a feasible construction, which could have been implemented with the technology of the time, the mid-sixties.

Further on in the description of the project, in the manner of an avant-garde art manifesto, he writes:

In a car-machine we drive

In a ship-machine we sail

In a submarine-machine we dive

In a plane-machine we fly

In a rocket-machine we soar

In a house-machine we reside.

And that is all.

Life will not thereby be inhuman.

That power of the spirit that has humanised all machines will humanise the house-machine too.3

Considering this positive attitude to technology and a consideration of its emancipatory role in architecture (which might overcome the force of gravity, Kokonplan, 1981), it is no surprise that in his work Mutnjaković also used digital technologies. He started using them in 1969 for the three-dimensional design of structures built in durable materials, in the framework of Croatian architecture probably the first, and in world terms among the first. Mutnjaković is an exceptionally productive and versatile author, engaged in architectural design, theoretical and historical research and set design.4

Mutnjaković took his degree in 1954 at the architecture department of the Technical Faculty of Zagreb University. Upon graduation, he worked as an assistant of Drago Galić, Lavoslav Horvat and Marijan Haberle, while from 1957 to 1960 he attended the post-graduate course in the national master-workshop for architecture run by Drago Ibler at the Academy of Fine Arts of Zagreb University. On the basis of his work to date, in 1961 the Croatian Council for Culture and Science acknowledged his status as artist, since when he has worked as a freelance professional. He has published numerous books from the domain of architecture (including Endemic Architecture, 1977, The Tertiary City, 1988, Kinetic Architecture, 1995) and the history of architecture (for example, The Early Renaissance City, 1991, Happy City, 1993, The Architect Lucijan Vranjanin, 2003). He is also much into journalism and social activity in the promotion of architectural creativity. He is a lecturer at the Workers' University in Zagreb, is a long-time member of the board of specialised publications (Čovjek i prostor, Arhitektura, Arhitektura i urbanizam), is president of the publishing council of the Association of Croatian Architects and founder of the imprint Architectonica Croatica of the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts. He is also a member of the presidency of the Association of Artists of the Applied Arts of Croatia known as ULUPUH, of the Association of Croatian Architects, and he initiated the formation of the Association of Freelance Artists of Croatia and of the Zagreb Salon, being president in the latter for two terms of office. He has received a number of prizes and commendations, including the prize of the Zagreb Salon (1968), the Grand Prix of the 20^th^ Slavonian Biennial (1985), the annual Vladimir Nazor Prize for Architecture (1991), the Annual Viktor Kovačić Architecture Prize and the Vladimir Nazor Lifetime Achievement Prize (2004) and the decoration of the Order of the Croatian Daystar with the figure of Marko Marulić for services to the nation. He has been a fellow of the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts since 2004, and is a member of the Society of the Brethren of the Croatian Dragon and of Matica Hrvatska.

Mutnjaković's works have been shown at a number of solo exhibitions (Initial Assumptions, Student Centre Gallery, Zagreb, 1969; Engaged Architecture, Gallery of Contemporary Art, Zagreb, 1975 and others) more than 50 collective exhibitions (Venice Biennale, 1991 among others) and have been published in numbers of journals at home and abroad, and been reviewed by many international art and architecture historians.

He has himself systematised his exceptionally rich oeuvre of architectural designs and town planning projects, accompanied with theoretical explanations, into four themes or problem groups. Among the many that he has classified under each theme we can find some built design that discreetly, but for us for significantly, used early digital technologies. We shall thus list all the themes, but devote our attention only to those projects that we are focused on here.

The theme we shall start with is the Analyses and design approaches for the reconstruction and revitalisation of the architectural heritage with an emphasis on the realisation of facsimiles where possible, with the employment of a contemporary expression based on indigenous quality of city or building. Among his other projects, Mutnjaković started the reconstruction and revitalisation of the Old City Town Hall (1720-1911) in Zagreb, which unfolded between 1968 and 1975 in several phases. This involved reconstructing and joining two neighbouring buildings in the Upper Town, in the oldest part of the historical core of Zagreb. While the project was being implemented, the client, the City of Zagreb, changed the purpose of space and hall, which continued after 1975.

Three rooms from the original Mutnjaković design are extant, still used by city councillors, but for different purposes than in the design. The primary purpose of these three rooms (chambers) was for sessions of the three city councils: the Economic, Culture and Education and the Social [Welfare] and Healthcare, to which the chambers are referred in the blueprint in 1970. A total design was produced in superb craftsmanship by a group of tradesmen who were permanent employees of the republic. All the furnishing was designed, and all other parts of the interior, down to the tiniest detail. The ceilings of the three chambers were designed three-dimensionally in ellipsoid forms like waves, and produced in coloured polyester. Each ceiling and each chamber was designed for itself, but on similar principles, setting up a strikingly impressive visual system. In the design of the ceilings of these rooms, digital technologies were used. In the accessible documents we can find descriptive programmes and computer printouts of these programmes, as well as plotter drawings that were used for the making of the ceilings. "The main curves were obtained according to the equation for a hyperellipse."5 The distances between neighbouring curves were in the progressive ratio of 1 : 1.1. On the digital plans of the designs of the ceilings of the chamber the cross sections are indicated, printed by plotter on standard paper for plotting (in a perforated roll). These printouts were enlarged on card in a real scale (stencils), which were used as an auxiliary means for the final rendering in undulating curves in polyester.6 The chambers had different sizes, and each ceiling was a new interpretation of undulating circular forms. Sources of light in the ceiling were out of the line of sight of visitors and gave a special dynamic to the whole space, sometimes in combination with the daylight that came in from the windows. The architectural blueprints for these three walls were officially handed over in April 1970, and along with the drawings of the ceiling (done according to the digital drawings) they included detailed technical depictions of the ceiling lighting system and many other drawings for all three complete chambers. Since the drawings were drafted by hand, for which a lot of time was required, the dating of the design of these three chambers and the digital design of the ceilings has to be put in 1969.

The Economics Council (today Chamber B) is the biggest of the three rooms for the separate city councils, but still a relatively small and intimate space in which are placed the maximum number of seats, which, for economy of space, are folding. The chamber has an 8 x 14 m rectangular plan, with a total area of 110 square metres, and is 412 cm high, with an undulating ceiling suspended 70 cm. With the exception of the spectacular ceiling done in polyester, wood is the dominating material in the interior. The upper part of all the walls of the chamber is done in wooden relief, rhythmically permutated by wooden balls of similar sizes in a dense grid.7 This striking visual horizontal extends through the whole of the space, interrupted only by the window frames, and expanded to the whole height via the relief appliquéd to the door. Applied in these reliefs are modular permutations of the basic geometrical forms, often represented in the aesthetics of the New Tendencies, achieving a dynamic and undulating rhythm, additionally impacted by the lighting and the movement of the observer. The chamber is entered from a space decorated in neo-Classical style in a palette of neutral pastel colours, which Mutnjaković also designed. The door leaves on that side of the chamber follow the neo-classical style of the room. The doors are shaped on each side in a different style and are harmonised with the design of the pertaining interiors when closed. When open, they start up a dialogue of the two styles, the modernist and the neo-classical, a concept that is applied to the whole of the reconstruction of the Old City Town Hall.

In the interior of the Culture and Education Council (Chamber C today), the shaping of the ceiling follows similar design principles, but in different shapes and colours. The same principle is applied in all three rooms, that of creating a horizontal that runs over all of the walls, under the undulating polyester ceiling, but in different materials. Along with the ubiquitous wood, here this horizontal is done on all the walls clad in leather modules of a total height of 161 cm. A module is a square panel (32 x 32 x 5 cm) clad in a digital graphic embossed on the light brown leather, that is, in a shallow relief, with no colour. Each leaf of the door is clad with same material. Unlike the design in the Economics Council, where dynamic variations of the same motif are applied on the wooden relief, in the Culture and Education Chamber the aesthetic of the repetition of the same motif is employed, and done in the material of leather. Light, with reflections on the material, again plays a role in the perception of the discreet depiction of digital graphics in shallow relief embossed on the leather.

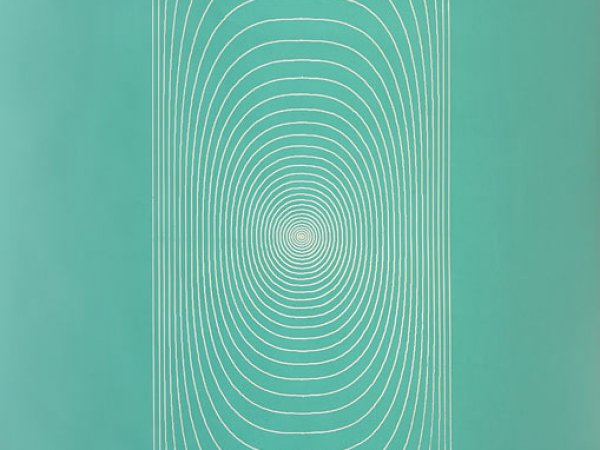

Used for the horizontal effect of the Social and Healthcare Chamber (today Chamber D) a grid of circular ceramic tiles along the wood walls is used.8 On the white tiles there are similar but variable blue digital drawings done in a slender line. "The graphic is founded on a simple algorithm of the distribution of a certain number of ellipses between two curves, between, for example, a circle and a spiral."9 By changing the parameters of the bearing curves various drawings are obtained with the application of the same algorithm. "The drawing begins in the mathematically initial point (middle right) and adds ellipses in a mathematically positive direction (anti-clockwise). The tiles are done in silkscreen printing in both versions so that in the chamber we can see segments in both directions - positive and negative rotation, and the initial point on the tiles is always middle top."10 The ceramic tiles were done after Mutnjaković's idea by the art ceramicist Hanibal Salvaro11 and were installed in 1971 and 1972. The role of Tomislav Mikulić in the work was related to programming on the IBM 1130 computer and the making of drawings via an IBM 1627 on a Calcomp 565 plotter, carried out in the Electrical Engineering Faculty in Zagreb. In order save on the paper used for plotting12 the phases of the drawing were printed out again on the same paper and photographed.13 At the end, all the phases in the development of the graphic motif were printed in blue in silkscreen technique on the white ceramic tiles, the surfaces of which shone in a transparent ceramic glaze.

In the revitalisation of the Old City Town Hall a new concert hall was planned. In the early 1970s a number of toilets were installed in the ground floor of the then atrium of the building, in anticipation of a fairly large number of visitors for the programmes of the future hall. Digital graphics were appliquéd to the ceramic tiles and doors of the facilities. But work on the making of this hall was stopped when the construction of the Vatroslav Lisinski Concert Hall started (it was opened in 1973). This whole toilet area was demolished in the subsequent reconstruction of building and atrium. The next digital graphic in the interior of the Old City Town Hall was appliquéd in the next phase of renovation, in 1973, on the leaves of the door at the entrance to two Wedding Halls on the 2^nd^ floor, when these halls were done in Mutnjaković's total design. The graphics were printed in silkscreen in white on green card, fastened onto the leaf of the door and laminated. These doors were taken away during subsequent renovation, but we can find out about the design process via the plotter printouts and the programme as well as the prototype impression on card sized 225 x 127 cm. But in the rooms of the two former Wedding Halls on the second floor, left today of Mutnjaković's interior design, we can still see the ceilings. They were rendered in relief rectangles, the compositions of which were also digitally designed, with the implementation of a progressive ratio of the following line of the square enlarged by 10%. Both ceilings were done in separate combinations of pastel colours. In the halls and in the corridor between them, placed in cupboards beneath the windows, are metal ventilation grilles, also digitally designed in 1973.

The next theme in Mutnjaković's systematisation of his own work is Studying the re-affirmation of national or regional architecture in a contemporary architectural idiom as essential factor for the de-alienation of the personality in the prevailing faceless setting of the contemporary city. Here there are seven designs that have not been built and nine that have, including the Kosovo National and University Library in Prishtina (1971-1982). The project was inspired by the reflections of Byzantine architecture in Catholic, Orthodox and Islamic architecture, creating the basic module of the building, which is also a visual sign – the cube with cupola. Rem Koolhaas says of the design: "Inspired by the shrine of Prizren (1563), it is one of the first buildings to have re-shaped the relations with traditional architecture. The idea for the free accumulation of a multitude of volumes, their autonomous organisation and illumination, makes this building an easily recognisable landmark".14 The modernist modular approach to the elements of the building (like a machine) is more than evident, but applied here in a visually richer version. In our focus on the digital, we will mention that in the brief of the building, on the fifth floor, alongside the Referral Centre, a room labelled Computer Processing was provided for. Digital technology was used in the design of the cladding of the walls of the Large Lecture Room (1979). The basic sign of the building, the cube with cupola, is to be seen in all the elements of the building, and its two-dimensional depiction in ground plan is a circle in a square. This two-dimensional sign was varied and permutated by computer into four complex images, used for the formation of the wall surfaces, done in wood.

The next theme in the author's systematisation of his work is Research into the employment of kinetic factors in the formation of building and city, so that boring static architecture can take on mobile properties and thus be communicatively at one with man. In these projects he applies the results of theoretical and practical research into the impact of kinetic factors on the design of buildings and cities, among which is the project Domobil of 1964 referred to in the introduction. One more unbuilt design to be considered here is the Most Beautiful House in the World15 (1989), designed for an international competition for a residence in Reggio Emilia in Italy. The house is imagined as a pavilion with a moving roof. The roof makes the space dynamic by opening metal roof surfaces at once, like a flower the petals of which open and close, or else partially, in various configurations that implement the brief of villa for living and relaxing in. The movement of the roof is activated by sensors or a programme, and is implemented by a hydraulic system driven by solar energy. Digital technology is used for the study of the oval forms of the ground plan, one of which is selected. "The proportional system of the axis is founded on the Pythagorean proportions of 3:4:5 as transmitted by Vitruvius and analogous researches into proportions, curves and spaces of Renaissance architects"16. In an explanation of the design, the author says:

The conception of the building as machine necessarily involved appropriate research into energy and technology, the wish being to create an autonomous system, programmed according to current and upcoming innovations... Post-constructional architecture is conceived according to the system of the machine. Of a communicative machine capable of satisfying human needs for flexible space. It has its bases in the double millennial understanding of machine as kind of architecture. It takes its perspective from the forecast categories of post-industrial society. There is a realistic chance that such an architecture, similar to the Ornithopter17 and ectoplasm18 will once again Renaissance-wise initiate the further paths of architectural knowledge.19

The fourth Mutnjaković theme in the systematisation of his work is Encouraging the application of bionic laws for the purpose of architecture and urban design as positive alternatives to the abstract schematisation of buildings and the space of the contemporary city. Here he included the Trešnja City Theatre (1964-1999). The façade of the building is a pixelated image, where ceramic tiles in various vivid colours are used as pixels, selected and distributed by computer, so determining the visual composition. The façade was produced in the final phase of the building of the theatre.

-

Andrija Mutnjaković, "Domobil", Kinetička arhitektura, Architectonica Croatica, Zagreb, 1996, p. 76. ↩

-

Single-family residences Mount Olympus Housing Project, Hollywood, 1964. ↩

-

Andrija Mutnjaković, "Domobil", Kinetička arhitektura, Architectonica Croatica, Zagreb, 1996, p. 84. ↩

-

The parts of the biography are culled from two sources: "Mutnjaković, Andrija", Hrvatska enciklopedija, online edition, Leksikografski zavod Miroslav Krleža, Zagreb, 2020. Accessed 17/9/2020. http://www.enciklopedija.hr/Natuknica.aspx?ID=42606 and "Akademik Andrija Mutnjaković", Članovi HAZU, Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts Website, Zagreb, http://info.hazu.hr/hr/clanovi_akademije/osobne_stranice/a_mutnjakovic, accessed 17/9/2020. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

The part of the production with plotter printouts and stencils was made a little easier by the ceilings being symmetrical, and only one side had to be done and then mirror-repeated in durable material. ↩

-

The wooden modules on each of which a pear-shaped ball was turned had a square plan, 9.7 x 9.7, while the balls had a diameter of from 6 to 9 cm. The relief had a height of 165 cm with 17 modules. ↩

-

Every ceramic circle was 14.5 cm in diameter and the total height of the 9 modules was 161 cm. On doors was a grid of 15 x 6 tiles (three on each leaf). The white ceramic tiles with blue drawings were covered with a wooden mask with circular cut-outs. ↩

-

Tomislav Mikulić, e-mail with the author, May 4, 2020. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

See n. 5 and the blueprint of April 1970. ↩

-

The roll of perforated paper was produced by Calcomp of the USA, as was the plotter. ↩

-

Ellipses drawn on paper with a plotter were photographed successively as they were indiviudally added to the same drawing. Salvaro photographed them with a TLR (twin lens reflex) camera using 120 roll film yielding 12 57 x 57 cm pictures. Graphic films used for silkscreen printing were used mirror-wise, to achieve the two directions of movement and double the number of motifs. ↩

-

Rem Koolhaas, Fundamentals Catalogue, La Biennale di Venezia, 14. Mostra Internationale di Architectura, 1991. ↩

-

La casa più bella del mondo. ↩

-

Andrija Mutnjaković, "Ornitottero", Kinetička arhitektura, Architectonica Croatica, Zagreb, 1996, p. 121. ↩

-

Planed designed by Leonardo da Vinci. ↩

-

The live matter of the cell consists of nucleus and cytoplasm. Protoplasm is enveloped outside by a plasma membrane, and in plants, fungi and bacteria also by a strong cell wall. In most plant cells the major part of their volumes is not composed of protoplasm but of a large vacuole wrapped in a membrane (tonoplast). In the cells of some eukaryotes the cytoplasmic part of the cell used to be divided into the outer layer, the ectoplasm, and the interior layer or endoplasm. Ectoplasm is dense, homogeneous and transparent, unlike the granular endoplasm, from which it also differs in its physical and chemical properties. The name protoplasm was brought in during the 19^th^ century; in modern biology it is rarely used for thanks to contemporary methods the previous unclear idea about a gelatinous live cellular matter was replaced by a clear image of the fine structure of nucleus and cytoplasm (from microscopic to molecular level). See "Protoplazma", Hrvatska enciklopedija, online edition, Leksikografski zavod Miroslav Krleža, 2020. Accessed 17/9/2020, http://www.enciklopedija.hr/Natuknica.aspx?ID=50769 ↩

-

Andrija Mutnjaković, "Ornittottero", Kinetička arhitektura, Architectonica Croatica, Zagreb, 1996, p. 128. ↩