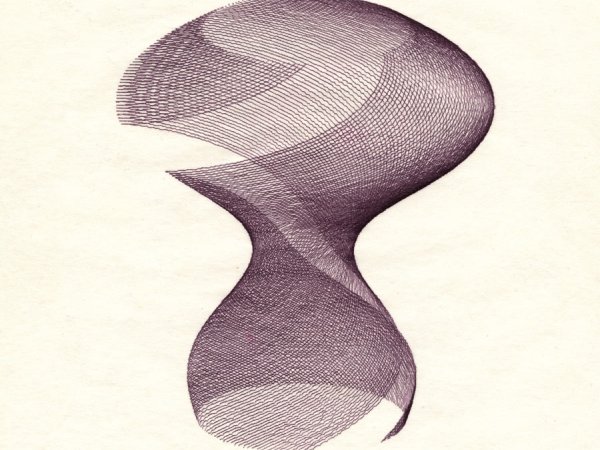

INSIN, 1972, digital printout / ballpoint pen, 29 x 21 cm

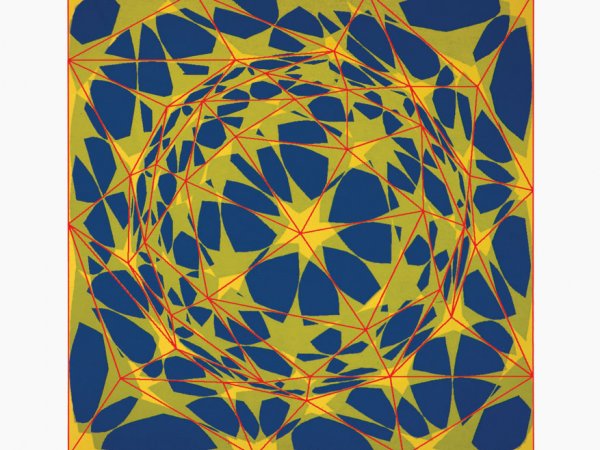

Network II, 1973, silkscreen, 33 x 32.5 cm

Network III, 1973, silkscreen, 33 x 32.5 cm

Green Sphere, 1974, silkscreen, 33.7 x 37.8 cm

*City lights, 1975., silkscreen, collage, 150 x 200 cm

Perspective green, 1974, silkscreen, 40 x 52 cm

Random, 1975, 2'14", 16-mm film

Red Squares, 1976, 35-mm slide

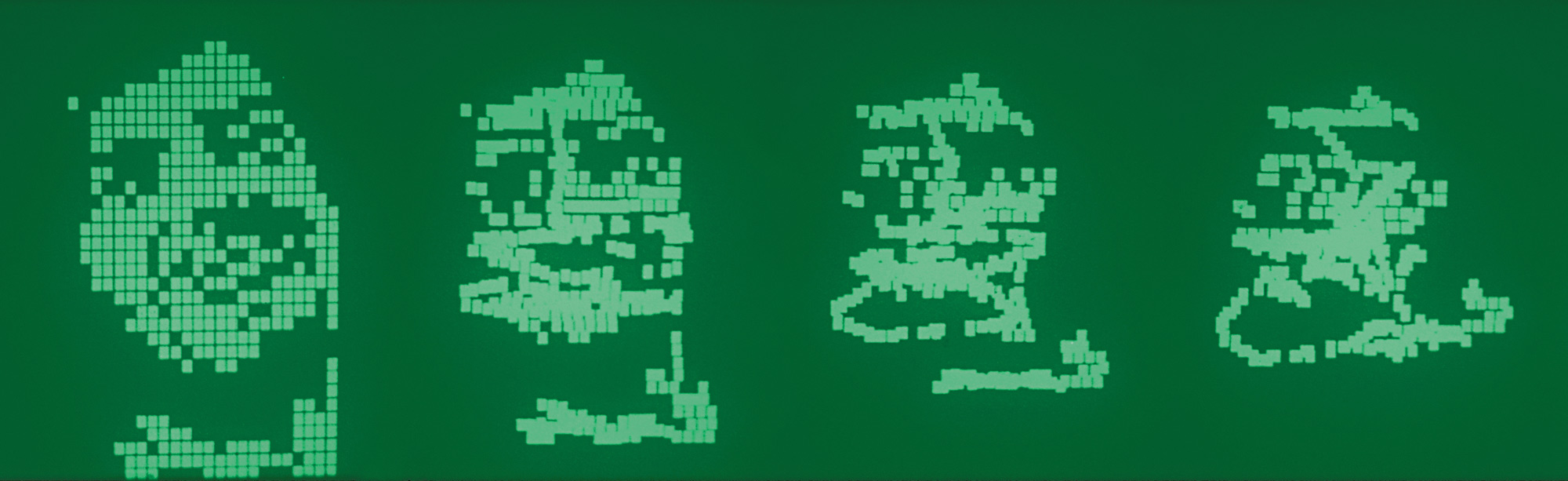

Morphing of Leonard Cohen into the Mona Lisa, 1976

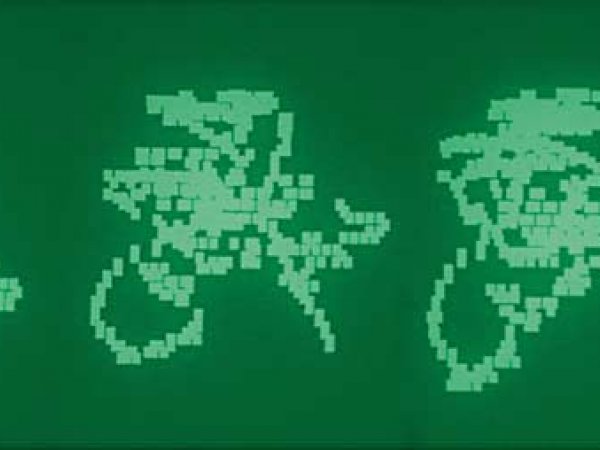

HP 2640A, 1975, 2'31", 16-mm film

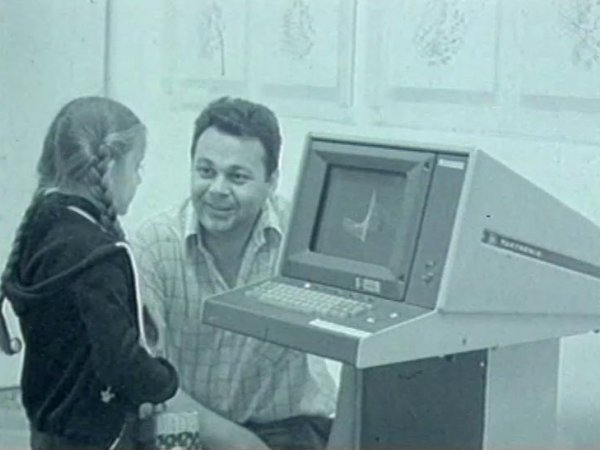

Mikulić exhibition, Nova Gallery, Zagreb, 1976

Tomislav Mikulić (1953) was first exposed to digital art when, as a fifteen-year-old living in Zagreb, as he recalls:

[he]saw computer graphics in American magazines around 1968... Then, thanks to a very good friend, Assefa, then a student of medicine from Ethiopia, from the time we had student exchanges with the Nonaligned Movement countries, I joined the reading room of the American Culture Centre at the embassy in Zrinjevac. I am endlessly grateful to the American government for letting us have free and unlimited access to American journals and accordingly an insight into the world state-of-the-art, about which we knew almost nothing from local publications. I recall Time and Life magazine issues, which published the famous Avedon psychedelic posters of the Beatles and photographs of Earth from Moon, taken by the Apollo astronauts. But I was incomparably more fascinated by the articles about computer graphics made by John Mott-Smith and Lloyd Sumner and the Calcomp Co. team. This planted a germ in me from which I was unable to recover.1

He learned the computer language FORTRAN when he was a pupil at the15^th^ Mathematics High School in Zagreb. He talks about his work of the time on digital equipment:

Then the time allowed for work on a computer was so precious that we wrote our exercises out on paper and only at the end of the half-year could we do the final programme on a real live computer. An indescribable experience! I enrolled in a course in the Electrical Engineering Faculty [EEF] of Zagreb University (today's Electrical Engineering and Information Science Faculty) in 1971 and started drawing my first graphics on the same computer and plotter... In 1971 I started really using the computer, mainly for drawing. An exception was the mandatory mathematics exercises that were part of the tuition, and for them too I liked drawing graphs, rather than calculating just the numbers. I had access to a plotter but then we had no ready-made drawing programmes. I had to programme it all and define every point in the drawing mathematically. In my earliest drawings, for example Elips and Torus it can be seen how I developed my software, the tool with which I was able faster and faster to draw increasingly complex compositions. Even the earliest, like Rotation, show the phases of the movement. My interest was from the beginning focused on animation, how to bring a drawing to life. Actually, it was a time of endless experimentation and curiosity. At the beginning I didn't see my drawing as a work of art, everyone was aspring board for changing something and making a new drawing.2

When the EEF offered him a job as instructor in the Computer Centre, having free access to digital equipment, in 1971 he made his first computer graphics in 1971. Mikulić by himself programmed every piece he made on an IBM 1130, and the graphics were drawn with ball point or ink on an IBM 1627 plotter, in fact a Calcomp 565 incremental drum plotter for 12-inch-wide paper. He was to use the same equipment for his artwork up to 1977. In parallel with his studies at the EEF, he enrolled in the graphic art course at the Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb "on the basis of hand-produced drawings that were totally unconnected with the computer".3 Mikulić graduated from this course in 1977, class of Albert Kinert, of which he recalls:

My former teacher and graphic artist Frane Paro told me years later I was the first Academy of Fine Arts student who did not do his graduation piece by hand.4

Mikulić transmits to us a particularly valuable testimony about the cultural climate and early digital art in Zagreb in the early 1970s from the standpoint of a young man:

Thanks to the reputation of Zagreb Film and the Zagreb School of Animated Film,5 we who had the luck to grow up in this cultural setting also had the chance to watch screenings of top pieces by authors like Norman McLaren and John Whitney. Under the aegis of Music Biennial Zagreb6 in the early sixties I experienced a performance by John Cage but also the audio-video-olfactory presentation that John Whitney Jr led in person. Then I saw for the first time his animated film Terminal Self, which kindled a new passion in me (a student who could just draw thin lines on paper in ink with a computer), and this was how to go off somewhere and try out equipment with these kinds of incomprehensible capacities. The exhibition tendencies 4 at which I saw actual computer graphics was a particular treat. At that time I adored Vasarely, Picelj and Knifer, and it was clear to me that the mathematical algorithms on which computer graphics were based were just a logical continuation of their constructions.7

In 1972, in parallel with the study of traditional graphic and drawing disciplines at the first year of the Academy of Fine Arts he produced a series of digital graphics that he started to exhibit. The works Torus and Nstar were shown at the 7^th^ Zagreb Salon in 1972, and nine prints were put into the exhibition tendencies 5 in the Technical Museum in Zagreb (today the Technical Museum Nikola Tesla) in 1973. In retrospect, their author says these prints "have elements of animation – drawings in time when I had no access to technology to animate them."8 He did not give his works titles until circumstances so demanded, as in the event of them being exhibited. Some of the works of this time, he would call Composition. At the exhibition tendencies 5 he showed computer drawings, the titles of some of which we can explain: INSIN – interrupted sine; SINCO – sine cosine; TORUS, ELIPS, NSTAR, NSTAR II and OVEYE (oval eye) and LINED of 1972, as well as a series of seven drawings named Rotation of 1972. Mikulić was to produce the animation Rotation some two years later in 1975.

In 1974 he created several groups of computer drawings. GRID is a series of three drawings in which distorted lines are distributed from centre out to edge. TRIANGS-SQ is a series of six drawings with triangles deployed in a rectangle, the origination, size and density of the triangles depending on their distance from the centre of the picture. The same parameters were used in a group of eight drawings – TRIANGS-CIRC – except that the triangles were arranged inside a circle. The WAVES group shows lines in six drawings that are defined by sinuses, the drawings differing according to various parameters of the trigonometric function.

Gallery of Contemporary Art in Zagreb issued a series of computer graphics, Net, three versions of the same picture done in different colours. An edition of 100 copies of each version was done in silkscreen printing in 1973.9 Serigraphy, in a larger edition, enabled a free use of colour and papers of various sizes, and he was to use the technique again in 1975 for the works City Lights and City Lines and in 1976 for the works Blue Perspective and Green Perspective. In 1975 Lithograph II (1974) and the collage City Lights appeared, combining analogue and digital printing techniques.

Studying the Old Masters at the Academy of Fine Arts, in examples like Rembrandt's Night Watch, Mikulić noted the effect of light behind some object in close up. In Lithograph II he applied this effect to a set of rectangular bars. With strokes of chalk on stone and the resulting irregularities he achieved a characteristic effect in lithographic printing in Lithograph II. In a computer programme he defined a pattern simulating the chalk texture and drew a module sized 25 x 35 cm with a plotter. A drawing in serigraphy was printed in black over a background consisting of five shades of blue. The collage was mounted on a canvas sized 150 x 250 cm. City-Lights (1975) was first shown at the 10^th^ Zagreb Salon in 1975.10 Composed in a similar manner were the lithograph Lithograph (1974) and the silkscreen print City Lines (1975), but here for the definition of the chalk texture Mikulić used an algorithm that changed the density of the lines (instead of the surfaces he used in the previous work).

Various media were used for the works from the series Perspectives of 1976, in which a perspective from two or three focal points was used. They were first produced in chalk drawing, then in acrylic on canvas, etching and finally on a plotter in a computer-aided drawing. Perspective 5 (1975) was exhibited at the first festival of Ars Electronica in Linz in 1979 in the Computer Graphic section. The same algorithm was used to make Blue Perspective and Green Perspective, which the author printed by himself in 7-colour serigraphy in1976.11

Mikulić talks about his graphics to that date and his access to more up to date technology, which started in 1974.:

The slowness of the plotter was not the only constraint of that medium. I wanted to see drawings of shaky ink lines in several layers and colours, which worked out for me in silkscreen. At that time I started using the graphic terminal Tektronix 4012 linked to an HP2000F computer in the Multimedia Centre of the Referral Centre of Zagreb University (MMC), in 1974. This was a huge watershed in my work. At the terminal I could generate drawings in minutes, not in hours, as with the plotter. Shooting the screen of the terminal in black and white 16 mm film I got countless short animated sequences.12

At the end of 1974 he worked on his first computer animated film in MMC. While he was still working on it and testing the programmes, in early 1975 he considered the option of how to produce it finally: "But the most difficult thing was still in store for me: programmes for the animation of several thousand drawings. And I had to find funding..."13 At last, the first digital animation (CGI)14 in Croatia was shot in 1975 with a movie camera, in which Mikulić was assisted by the cinematographer Vladimir Petek. The first sequence showed the squares morphing into squares including the number 1975 at bottom, which signified the year of production.15 This and all subsequent Mikulić computer generated images from the screen of the Tektronix 4012 in the MMC were shot on black and white 16 mm film with a Beaulieu R16 movie camera.

In 1976 he put on his first solo exhibition in the Nova Gallery, Zagreb, where the first Croatian digitally animated film was shown, as recorded in Encyclopaedia of Film: "The first computer film in Yugoslavia was made and publicly presented in 1976 under the title 2548A. The author, Tomislav Mikulić, used the screen of the graphic terminal Hewlett-Packard 2548A for the shooting."16

The author himself gives an earlier year of production, 1975,17 as noted on the film and that fits in with information from an interview published in the magazine Start in February 1975, in which in the phase of testing the computer programme as beginning of the work on the film the end of 1974 is implied.18 He also thinks that the film Random (1975) was the first Croatian digital animated film, for it was the first such film to be made as a whole.

Mikulić was then using the programme languages FORTRAN, Assembler and BASIC, and developed numerous programmes, algorithms, such as Morphing (1973) for turning one object into another and Parametric Font (1973), in which letters could be written out and manipulated. These two algorithms were employed in the following example. On a poster for Mikulić's exhibition in Nova Gallery in 1976, ten phases of the morphing of the word Text into Image were shown. The pictures were taken out of an animation sequence lasting 8 seconds (Transition of text into image, 1972-1975), shown at the exhibition, alongside the film already referred to, Random. When the poster for the exhibition is looked at as a whole, after information about the gallery and opening times in the top part, the typographic unit begins: "TEXT / IMAGE MIKULIĆ WITH COMPUTER: FILMS MULTIVISION PLOTTING DRAWINGS SILKSCREEN".19 The central and most important part of the poster, usually reserved for a reproduction of a work, consisted of a phase in the morphing of the word TEXT into IMAGE, while under that in the biggest font is written MIKULIĆ, as is appropriate for the design of a poster for a solo exhibition. The rest of the text about the media presented is shown in lower case.

In film documentation about the Nova Gallery exhibition in 1976 which, by good chance, is accessible even today, along with the visitors and the many graphics shown on the walls of the gallery in the manner of a classic gallery presentation, numerous items of computer and film equipment are noted, along with slide projectors handled by the author and his assistants.

The programme Computer Animation was shown in Nova Gallery in Zagreb from June 16 to June 20 1980. The programme, which was conceived20 (curated, according to the current terminology) by Mikulić, presented a cross section of international work in artistic digital animation, from already historical examples (Whitney, works from 1961 to 1971; Vitkine, from 1968 to 1979) to recent productions (Huitric and Colonna). Films and slides were screened, and on monitors video from cassettes was running. Herbert Franke demonstrated on a computer his own art computer programme MONDRIAN. Local authors involved were Mikulić, with a compilation of animations on video tape, and Vilko Žiljak, with slide projections. Also presented were several corporate promotional videos about the most up to date achievements in digital animation. The programme was shown during the four days, from 6 pm to 8 pm, and every day after the programme, Julije Makanec would demonstrate the graphic capacities of the Apple II computer. Today we would call this kind of programme a festival. The periodical press gave a detailed description of the programme and made comparisons with the International Festival of Animated Film in Zagreb, which then still did not accept electronic video format for the presentation of computer animation, and made the observation: "The public consisted of people who were not only into animated film, but who understood computers, and had no need to be persuaded about their advantages."21

Many artists, curators and organisers were reflecting on the challenges of the public presentation of time-based digital art. In the context of gallery exhibition of fine art, special happenings were often organised, whether as performances during the opening, or whether as side events, such as programmes of film screenings or video projections. In the 1970s video monitors were introduced as standard features in gallery exhibitions, as were video projections in the 1980s and PCs with monitors and projections of digital data in the 1990s. Film projectors, as a vintage chic trend of contemporary art in the 1990s, projected 16 mm and 35 mm celluloid loops in prestigious galleries and museums. Finally, triggered by mass usage and the plummeting prices of digital equipment, in almost all galleries after 2010, a standard of digital projects with digital formats was established. For the presentation of time-based media art, from the 1980s the format of exhibition was increasingly replaced by that of festival, occasionally with side exhibitions. Since time-based media art was often changed and redefined, from the 1990s the presentation formats changed, often using extra-gallery hybrid platforms, such as the Internet and wet-labs for bio-art. Sometimes presentations unfolded in public space, as was the case with media-facades, actions with tactical media, performances with locative media (using GPS) and sound-walks and so on.22

Mikulić reminisces about the format of the presentation of early digital animations:

When my works became just animation, when they stopped being on paper, I no longer had traditional exhibitions. My solo shows started to be one-evening projections. The only trace they have left is in the posters. In a similar manner I also had presentations in TV broadcasts.23

So, apart from gallery exhibitions, Mikulić did his public presentations in other formats. One was the "auteur's film evening", taken from the film world, an example of which was Mikulić's evening programme Computer animation in a cinema, that of the Student Culture Centre in Zagreb in 1979.24 After that was the lecture or artist talk, such as lectures at the symposium Artist and Computer in Paris in 1979.25 A poster for the 1979 film evening bears a reproduction of the work Mona Lisa, the last phase of the morphing of a picture of Leonard Cohen into the Gioconda. The two-metre-high poster was printed in silkscreen technology, and was designed by Mikulić.26 In 1978 a colour version of this work was reproduced on the cover of the book of Herbert Franke Kunst kontra Technik?27 The animation was shot from the screen of the Tektronix 4012 terminal with a 16 mm movie camera on black and white stock, subsequently coloured with electronic video equipment. It was made in 1976 for the new opening sequence of the show Hi youngsters, a popular infotainment broadcast of Zagreb TV from 1970 to 1987, winner of the TVZ medal for youth creativity.

The broadest format of presentation in the second half of the 20^th^ century was without doubt the TV, which Mikulić often used in various ways. He appeared on TV Zagreb (today HRT) not only in a reportage about his solo exhibition but also in two presentations of MMC,28 in which he introduced his animations and interpreted them from artistic and technical aspects. He carried out a kind of appropriation of the TV broadcast as artistic medium in the broadcast TV Exhibition shown on TV Zagreb in 1988.29 The author says:

TV Exhibition was a series of shows about artists. All previous broadcasts had shown the selected artist in their studio, details of the work, painting or engraving. There were few works shown, few pictures were shown, a bit of the artist working. In the background they had music and there was no commentary or voice-over. Editor Vesna Mahečić was very trusting in giving me a free hand at directing the broadcast about my work myself. This was a precedent, for TV Exhibitions showed how an artist created certain artistic works. In my case actually the broadcast was the work of art and showed how it came into being. The reviews took it to be a big move forward and thought it refreshing. It was broadcast several times.30

The animated video Dance (1979, 6' 30'') was made in collaboration with dancer Zagorka Živković, who appeared in a virtual, computer-animated space. It was shown in the official competition of the World Animated Film Festival in Ottawa in 1980.31 It was the first film festival to accept films in video format.32 For electronic films, that is, the video tape was an original medium in which works were created, but the festivals had previously insisted on celluloid. Not only did this entail unnecessary costs with film stock but there was also a problem with quality of image: in the transfer from electronic to chemical medium, some deterioration in the quality would occur.

Mikulić independently had important results in TV graphics. For technical reasons the EBU Eurovision logo33 used for international TV broadcasts was always transmitted from static slides. Mikulić made the first animated opening title for the Eurovision 1979 broadcast and enabled TVZ to be the first station in the history of the EBU to have made and broadcast an animated Eurovision logo.34 "As head of the department of TV design in set design of TVZ from 1980 to 1991 he left a deep mark by the creation of animated title sequences for most of the broadcasts (News, Programme Plus, Saturday Night, Quizbox and others)".35 He led a team of 18 authors who developed the visual components for the channel and for TVZ. He produced the animated title sequence for the Winter Olympics in Sarajevo in 1984. He remarks as follows about this experience:

TVZ had a Flair graphic station that could store digitally just one static image. It could not generate an image through programme or algorithm. At that time I already had my own computer at home (DAI)36 which I could programme but the image I could save was of too low a resolution for this kind of operation. To make the computer animated title sequence for the Olympics, the only solution I could see at that time was to write and produce animation on the DAI, the results going to Flair in high resolution. After some incredible hardware-software acrobatics, a key role being played by colleague Antun Šernhorst setting up a hybrid system, the project succeeded and my animation for TVZ took the first place in the competition and was shown worldwide."37

In Melbourne, to which he relocated, in 1992 he founded his own studio for animation and graphic design, called High Resolution Design Studio.38 He developed the graphics for the Virtual Sports system, including visual components for the virtual yellow line for swimming races at the Sydney Olympics, 2000. His animation was chosen by Autodesk Inc., which included it in its showreel at SIGGRAPH 96. In the same year he was one of three animators nominated for the top Australian prize for animation – the annual award of the Australian Festival of Effects and Animation. From 2002 to his retirement he worked in the Advancement team in Monash University. He won a competition for art and design of Melbourne City Urban Forest 2011, just 40 years after he had produced his first computer graphics.

-

Tomislav Mikulić, Darko Fritz, structured conversation, April 2020. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

"The Zagreb School of Animated Film is an aesthetic term for a school of animation that in the mid-1950s took an avant-garde step forward for a new generation of lovers of animated drawing. Seventeen authors with a single common desire created diverse animated works, but in them we recognize a new concept of animated film. In the only complete book on the Zagreb School, Z is for Zagreb, film critic Ronald Holloway calls the period from 1957 to 1962 the golden period of the Zagreb School of Animated Film. It is represented by the authors Nikola Kostelac, Vatroslav Mimica, Dušan Vukotić and Vladimir Kristl. The first world success of the Zagreb School of Animated Film was the Grand Prize of the Venice Film Festival for the cartoon The Bachelor by Vatroslav Mimica, and the golden period ends with the Oscar for the film The Surrogate by Dušan Vukotić in 1962. From today's, slightly more distant perspective, it can be concluded that even with the great crisis at the end of the 1970s and 1980s, this unique school of animation gave the European film heritage more than 400 titles of worthwhile animated works that were awarded more than 400 of the most prestigious awards around the world. Zagrebačka škola crtanog filma, O Zagrebačkoj školi, Zagreb film, accessed 12/9/2020. http://zagrebfilm.hr/o-nama/zagrebacka-skola-animiranog-filma ↩

-

Music Biennial Zagreb (MBZ) is an international festival of contemporary music. Initiated by the Croatian composer Milko Kelemen at the end of the 1950s and first held in 1961 it is still continuing, making it one of the oldest festivals conceptually oriented in this way in the world. The original goal of the Biennial, according to Kelemen's original idea, was to inform the Croatian community about current events in contemporary music in the world and thus enable contemporary Croatian music after World War II to be made current. From the very beginning, the Biennial or Biennale was distinguished by its broad conception and non-attachment to any ideologies, so it was often regarded as a musical-cultural bridge between East and West, mainly because its programmes featured composers who could not be performed on the other of the 'Iron Curtain'. In its rich history, it hosted almost all important composers and performers in the second half of the 20th century.\"Muzički biennale Zagreb\", Hrvatska enciklopedija, online edition, Leksikografski zavod Miroslav Krleža, 2020. Accessed 12/9/2020, http://www.enciklopedija.hr/Natuknica.aspx?ID=42629 ↩

-

Cf. n. 1. ↩

-

E-mail correspondence, preparation for a talk by Darko Fritz at the event 40 years of computer animation in Croatia,1976-2016, Technical Museum Nikola Tesla, Zagreb, June 9, 2016. ↩

-

Three pieces from the Net series are in the collection of the Zagreb Museum of Contemporary Art. ↩

-

City-lights is in the collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art. ↩

-

Later there was an animation of a square in colour in 3D space, Perspective in smoke (1998). ↩

-

Cf. n. 1. ↩

-

Damir Mikuličić, "Zaboga, Starte, što ću s vama", Start, no. 158, Feb. 12-16, 1975, Vjesnik, Zagreb, p. 18. ↩

-

CGI: Computer-generated imagery. ↩

-

B/w 16 mm film. Now in the archives of the Museum of Contemporary Art Zagreb. ↩

-

"[Computer Film]", Filmska enciklopedija, vol. 1, JLZ Miroslav Krleža, Zagreb, 1986, p. 712. ↩

-

Cf. n. 1. "In 1975 I shot the first computer animated film, Random in Croatia (CGI). It was shown in public at my first solo exhibition in 1976." ↩

-

Cf. n. 13. ↩

-

Poster, 100 x 70 cm, silkscreen, Nova Gallery, Zagreb, 1976, Design: Mladen Galić. ↩

-

Computer Animation, catalogue, Nova Gallery / Centre for cultural activity, Zagreb, 1980. Concept: Tomislav Mikulić, Organised by Nova Gallery in association with the Culture and Information Centre of the BRD in Zagreb. ↩

-

Darko Zubčević, "Crtići kiselao smijeha [Sour smile cartoons]", Start, no. 299, July 9, 1980, Vjesnik, Zagreb, pp. 72–74. ↩

-

Mikulić produced two interactive installations in public space: Portraits of filaments, 2015, media façade, Museum of Contemporary Art Zagreb and The Eyes, 2017., installation, 3-channel, Kingston Arts Centre, Moorabbin. ↩

-

Cf. n. 1. ↩

-

November 20, 1979 at8 pm. ↩

-

The symposium accompanied a collective exhibition of digital graphics -Artiste et ordinateur, Centre Culturel Suedois, Paris, 1979. ↩

-

The poster, sized 198 x 138 cm, was printed in silkscreen technique and was composed of four parts. ↩

-

Herbert Franke, Kunst kontra Technik? Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt, 1978. ↩

-

Autor i oprema [Author and equipment], MMC, interview of Branko Nodilo, TVZ, duration 1 min, 1976.; O radu, MM Centar, interview of Ingrid Černi, TVZ, duration 1' 30'', 1976. ↩

-

Tomislav Mikulić: Tomislav Mikulić, TV Exhibition, 1988, 8' 15'', video. Produced by: TV Zagreb. Editor of the TV Exhibition series: Vesna Mahečić ↩

-

Cf n. 1. ↩

-

Ottawa International Animation Festival, 1980. ↩

-

Cf. n. 1. "I was a member of the organising committee of the Festival [of animated film in Zagreb] held in 1978 and I had presentations to the other members to persuade them we should seek a change in the rules in time to be able to include computer animation from the world in the 1980 programme. This alas did not take place, but at the festival I talked with John Halas, president of ASIFE about the change. It was June 1980 that we learned that the Ottawa Festival was going to accept videos in August, two months later. ↩

-

European Broadcasting Union (EBU) ↩

-

Cf. n. 1. ↩

-

"Mikulić, Tomislav", Leksikon radija i televizije, Hrvatska radiotelevizija, Naklada Ljevak, Zagreb, 2016., p. 327. It also says: "Particularly noted were his animated title sequences for international evens (Mediterranean Games, Split, 1979; European Swimming Championships, Split 1981; Winter Olympics, 1984; European Basketball Championship, Zagreb 1989; European Athletics Championship, Split, 1990; Eurosong in Zagreb, 1990, and other events). He animated the Eurovision logo in 1979, and TVZ went down as the first television to broadcast it in motion. ↩

-

From 1981 to 1984 Mikulić used a DAI PC. ↩

-

Cf n. 1. ↩

-

He worked in TV in Australia as well; in 1998 he joined a team that did virtual graphics for Channel 7. ↩