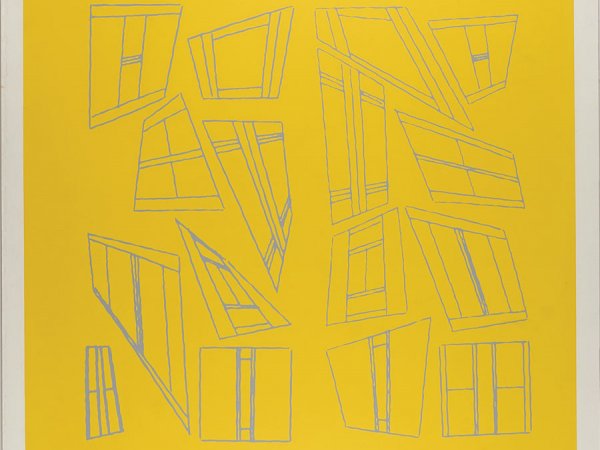

Conversation C2, 1973, silkscreen, 33 x 101.5 cm [MCA]

Conversation C3, 1973, silkscreen, 33 x 32.5 cm [SK]

Conversation C4, 1973, silkscreen, 33 x 32.5 cm [SK]

Miljenko Horvat and Serge Poulard (Cygra 4): Computer Triptych plus one, digital printout, 28 x 81 cm [SK], Canadian Statistics, 1971, title page of journal, offset, 28 x 20.5 cm [SK]

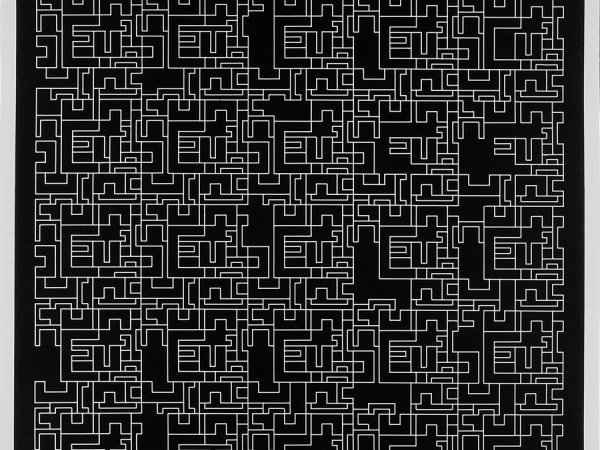

Unknown title, from the Eratos series, 1974, silkscreen, 62 x 43 cm

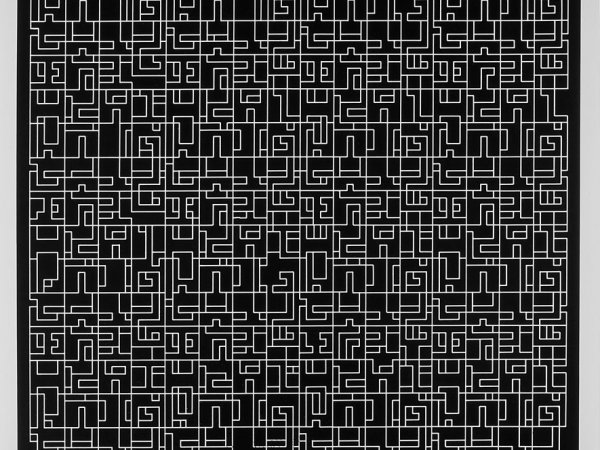

Unknown title, from the Eratos series, 1974, photograph of digital graphic, 19 x 20 cm

Unknown title, from the Eratos series, 1974, photograph of digital graphic, 19 x 20 cm

A position apparently diametrically opposed to the rational art of members of the New Tendencies movement (NT) can be seen in the work of the proto-conceptual group Gorgona of Zagreb, which was at the peak of its activity between 1959 and 1964.1

Gorgona did not have its own formal style, nor did it make public pronouncements of the manifesto kind typical of the avant-garde groups of the era. The activity of the group was of a primarily private nature, and included behaviour as artistic act. This included for example joint strolls in nature (given the name commission audit of the beginning of spring), an ample correspondence written in an archaic and jocular language, and antedated to a century earlier, working meetings with homework and various questionnaires (for example with thoughts for a given month) and the imagination of various projects at a conceptual level and on the whole never produced.2 Because of the great variety of artistic discourse, it is a little confusing that of the nine members of the Gorgona group, as many as five also took part in the NT, which proclaimed rational, constructive and committed approaches to art and society. Obviously we cannot address this issue through a linear historical framework. Working in Gorgona were the painters Josip Vaništa, Marijan Jevšovar, Julije Knifer and Đuro Seder, sculptor Ivan Kožarić, art historians and critics Matko Meštrović, Radoslav Putar and Dimitrije Bašičević Mangelos as well as architect, painter and photographer Miljenko Horvat. Matko Meštrović was the co-curator of the first exhibition, one of the initiators of NT and its leading theorist, while Putar and Bašičević were employees in the Gallery of Contemporary Art and organisers of the Zagreb NT exhibitions and, like Meštrović, members of the editorial board of bit international. Julije Knifer showed his work at the first, second and fourth Zagreb NT exhibitions, Mangelos at tendencies 4 in 1969 and Miljenko Horvat exhibited computer graphics in the exhibition tendencies 5 (1973).

Gorgona organised a number of shows in the off-space of the Schira Salon, which they referred to as Studio G. They organised exhibitions not only for their own works but for those of other authors as well, including participants of NT François Morellet (1962) and Piero Dorazio (1963). They published the anti-journal Gorgona, which Josip Vaništa, the initiator of the group, imagined as a number of distinct author works, which from the standpoint of contemporary discourse we can see as a forerunner of the form artist book. Issues of Gorgona were published by Dieter Rot (participant of NT in 1961) and Victor Vasarely (NT 1973). Because of lack of funding, the journals of Piero Manzoni (1961), Enzo Mari (NT 1963 and 1965) and Ivan Čižmek (NT 1965) were left at the level of mock-up, as were those of Ivo Gattin and Marijan Jevšovar.

Group member, historian of art and eminent art critic Dimitrije Bašičević, whose artistic name was Mangelos, suggested that one number of the journal be skipped, and this missing number be presented as his author's edition. Vaništa turned this suggestion down. Mangelos published a different author's journal as part of the imprint "a", which was personally published by that prominent NT participant Ivan Picelj. Picelj launched "a"3, as a series of journals, in 1962, advocating "an active art", rationality and "subordination to a higher structural order",4 which were value categories diametrically opposed to those in the work of Gorgona. Mangelos' proposal for an exhibition in Studio G was also rejected, and with the exception of his edition of "a" among the rare public presentations of his art work in the 1960s was his participation in the exhibition of typoetry in 1969, part of tendencies 4. Mangelos began to present his works publicly only from the 1970s, but because of the mystification and planned ante-dating of his art work, we can only guess at whether he really started producing them from the 1950s.

In the activity of NT the approach was open, rational, leftist, anti-bourgeois and socially engaged over a wide field, oriented to the future, following the avant-garde and modernist logic of negating history and re-examining the world from the beginnings. On the other hand, in the work of Gorgona, the approach to art and world was extremely individualistic, poetic, witty, nihilistic, offbeat and absurd, backward looking, supportive of the tradition of a middle class disappearing in the socialist surroundings of Zagreb of the time and hence politically conservative. Here was the main difference between Gorgona and the Situationists, who also in the 1960 promoted behaviour as an art form. Both discourses were avant-garde and they were linked by a radical conception of history and the historical moment they occupied, but they understood them very differently. From this derive the diametrically opposed understandings of their roles in society. On the one hand, Gorgona was marked by an existentialist philosophy, by absurdity and nihilism, playing at setting up some parallel cyclical time of their own, and retreating from society into private life. On the other hand, NT wanted to create a new world, from the ground up, and in this they saw their role rationally, openly, actively and constructively. Both discourses though were linked by the avant-garde concept of eliding the borders between life and art. In other words, Gorgona cultivated no hope that science was going to bring progress, while NT firmly believed in this, promoting it in all fields, including art, design and politics. Taking into consideration the overlaps and simultaneities of the two different concepts of art in the framework of which the artists, art historians and theorists mentioned worked, it would seem that the linear history of art cannot be applied to the Croatian art scene of the 1960s, if at all. This seemingly schizophrenic image can seem clearer to us with respect to the advocacies of individuals in public through ideas that gradually formed the cultural mainstream (for example, the work of Meštrović, Putar and Bašičević as art critics and promoters of NT ideas) and other parallel interests that were outside the framework of public activity and a certain historical moment, such as the private, poetic, invisible, absurd, non-rational and socially uncommitted works of Gorgona.

At the time of the actual working of Gorgona, its work was not appreciated by the wider social setting, although its members were prominent participants in the art scene as artists, organisers and critics. Gorgona works were appreciated more widely only after subsequent contextualisation of the work of the group through the theory and practice of non-object (conceptual) art, i.e., the New Art Practice of the late 1970s.

Miljenko Horvat (1935-2012) was author of the issue of Gorgona no. 7 of 1965, of which Marija Gattin said:

Every number contains two enlargements of different exposures of the same shots of the shore in Skagen, Denmark. This shore with its dead gulls is mentioned by Miloš Crnjanski in his travelogues, and this is the reason for Vaništa's visit to Skagen. Prompted by Vaništa's story, Miljenko Horvat also paid it a visit, in September 1963 and did indeed see dead gulls, which he photographed and sent to Vaništa. One of the photographs was selected for the journal, and, repeated in a lower exposure, it gave this publication of Miljenko Horvat a markedly poetic tone.5

Trained as an architect, but also a dedicated artist, painter and photographer as well as Gorgona member, Miljenko Horvat lived in Paris from 1962 to 1966 and then in Montreal, where he took a degree in art history. He had his first solo exhibition in 1961 in Zagreb, and in the same year took part at the second Biennial of the Museum of Modern Art in Paris. He showed paintings, drawings, prints and photographs at more than 150 collective and individual exhibitions in Europe, both the Americas and Japan. Many of his works are to be found in museum collections, including New York's MoMA.6

The Digital Art of Milan Horvat

In 2000, as curator, I was selecting works of early digital art from the collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb, preparing the exhibition I Am Still Alive.7 Then there was no list of the collection in digital form, and no way of searching, and I made the selection "manually", going through the book of all the works, some of which were not reproduced.8 Knowing then the work of Horvat only as a member of Gorgona, painter and photographer, I never even guessed that four prints in silkscreen called Conversation C 1-4 of 1973 were in fact computer graphics. And so it turned out that on that occasion I failed to put his work into the show. It also turned out that I Am Still Alive showed works of early computer art from the 1960s and 1970s for the first time, in world terms. In fact, in 2000, few people were dealing with computer art worldwide, and neither it nor the New Tendencies movement was a matter of current interest. At a later date, studying the NT more attentively, I found out that Horvat had exhibited computer graphics at the exhibition tendencies 5 in 1973, but the surname Horvat is extremely common in Croatia and for several years I still did not grasp that it was the same person, that the member of Gorgona was that same artist or author.9 Finally, I include his computer graphics at the exhibitions about the New Tendencies in Graz and Karlsruhe (2007-2009). Miljenko Horvat vigorously created and exhibited computer graphics from 1971 to 1977,10 but after 1977 this was not easy to spot.

Asked by Alexis Lefrançois what his "currently favourite technique" was in 1980, Miljenko Horvat replied: "Hard to say. I'm always drawing and painting. I also do lithographs... My work is gestural."11

Art media are mentioned again in that conversation.

A. L.: You have used a mass of different means of expression -- photography, collage, painting, drawing, engraving. Does the use of a given technique correspond to a certain phase of development or did you use them all at the same time?

M. H.: I've always used several techniques concurrently. I started off with drawings in ink and pastel; I also painted, first in oils, then in acrylics. As for photography, I think it an activity in itself. It needs to be distinguished from the photographs that I use as a building element of the image in my collage. For example, in Paris between 1963 and 1966 in winter I photographed completely bare trees and did high contrast prints. I photographed the empty streets, uncommon places, and later, in New York and elsewhere, walls, inscriptions, graffiti, torn posters. I exhibited some of these photographs as "photo-collages". But as for my painting work in the real sense of the word, I liked picking up used up filthy things, trash -- no nostalgia involved at all -- and using them as building and colourist elements. Instead of laying down colour with brush, I did that by incorporating into my collages cut out, torn out elements, which seemed to people realistic or anecdotal, but were to me actually not. It is sometimes hard to explain that for me they are just triggers. They set off the origin, development and growth of the picture. Between approximately 1972 and 1975 I used some parts of the female body as a point of departure. I called it natural geometries. (...)"12

In this conversation Horvat nowhere let it be known that he was the author of numerous carefully mathematically constructed graphics of abstract depictions, which he did from 1970 to 1974. In terms of the content of the answer, it cannot be guessed at even. But Horvat is an author who surprises, he is the embodiment of the thesis about the non-linear understanding of art. He is a member of Gorgona, where he produced anti-art, a painter who in his art used gesture, an art photographer, and also carried out the visual research with a computer specific to the NT. Each one of these segments of his work can only with difficulty be connected with some other segment, whether visually or aesthetically. As architect and artist, he understood geometry, which is the basis of his digital abstract graphics, in very different ways, as he mentions in a conversation with Raymond Gervais in 1976.

R. G.: Why did you use the triangle as the basic figure?

M.H.: Don't imagine I used only triangles! I also did squares, I called them natural geometries There's nothing special behind it, no kind of obsession. I was inspired by the female body of course, but as soon I started working, it was turned into an exercise in form. That's all. No need to spend too much time on it. Incidentally, hasn't the body of a woman been an inexhaustible source of inspiration for artists since prehistory?

R. G.: Art and the computer, isn't that a manner of setting up a balance in your work?

M.H.: I think it is. That's important for me. From time to time I need that effort of computation. For example, my geometrical pictures of 1970, 1971 and 1972 [computer graphics] in which there is nothing automatic, they were a kind of reaction to what I had done until then. It was very draining. It required a fair amount of effort, for I had to calculate the proportions precisely and to think hard to get a satisfactory composition. I felt the need, as always, to impose a certain discipline on myself."13

The interview with Horvat that was carried out, probably by letter, by Ruth Leavitt in October 1975 and published in her book Artist and Computer, is worth citing in its entirety: 14

"Miljenko Horvat: I don't have any particular theory or philosophy about my work. I try to do what I like and what I can, technically speaking. So I shall attempt to answer your questions as sincerely as I can.

How/why did you start working with the computer (art works)?

– I was open to it, or almost open, and tried it, and I liked it.

What kind of artwork had you previously been engaged with?

– I was a painter from the mid-fifties.

What role does the computer have for you -- simulation, tool and so on? What is your role?

– It's a very fast tool.

Are your digital works connected with your non-computer art?

– No, or very little.

Do you have in mind the ultimate image when you start work?

– Yes, but not always a very clear one.

Can you do your work without the help of a computer? If so, why then use a computer?

– Naturally, it could be done without a computer. But to produce the same quantity of works, I would need several thousand times as much time and energy, which I can't afford.

To what extent are you involved in the technical production of your work, in programming for example?

– I work very closely with Serge Poulard, an excellent programmer.

Do you think that a work of art made with a computer has now or will have an influence on art in the future?

– Now it has very little influence on art; I hope this influence will increase in the future.

Do you recommend the use of the computer for the creation of artworks to others?

– Yes, but only if the use of a computer is justified by the creative needs or sensibility of the given artist."

Lucija Dujmović Horvat, his widow, tells of how Miljenko Horvat started to deal with digital art:

Miljenko started working in the Audio-Visual centre in Montreal University in 1969, as designer of promotional material for the university. He got to know Gilles Gheerbrant, who got a French scholarship from the Conseil des Arts du Canada to write about Marshall McLuhan... Both were lovers of art and hung out together. This was the beginning of several years of working together, first in the university computer department, which was also run by a Frenchman, Serge Poulard. After work they would meet in his room and start experimenting and exploring the possibilities of creating art with a computer, which went on for the next few years. At the same time faculty members in other universities in the world (Germany, the US) started to explore the possibilities of computers for artistic expression (Georg Ness, Frieder Nake, Manfred Mohr, Manuel Barbadillo, Kenneth Knowlton and Hiroshi Kawano), Miljenko and Gilles got them together and published at their own expense the portfolio Art ex Machina, with a foreword by Abraham Moles. Miljenko and Gilles made all the decisions together, but chose just one name under which to work, Gheerbrant. Together they planned the activities... Art ex Machina. Mljenko contacted the artists, ran the correspondence, they oversaw the printing together. It was all very demanding, they split the costs.15

The portfolio Art ex Machina, released in Montreal in 1972, edited by Gilles Gheerbrant and released only under his name was probably the first ever portfolio of computer graphics to be published in the world.\ In addition, from 1972 to 1973 Miljenko Horvat and Gilles Gheerbrant produced the edition 1+1 (one artist, one poet), in which they published some digital graphics, again one from Manfred Mohr and probably the only computer graphic made by the Canadian experimental film-maker Norman McLaren, clearly at the suggestion of the publisher. Gheerbrant also ran a gallery, in the work of which Horvat took part, exhibiting as well. In 1972 Horvat was the co-organiser of an international exhibition of computer art in Montreal, at which he too exhibited.16

At the university where Horvat was employed from 1970, he worked with members of Cygra 4 (Cybernetic Graphic and Animation Group), which lists him as associate of the group along with a few visual artists and musicians. Members of the group were head of research and special projects of the Audio-Visual Centre GIlles Gheerbrant, programmers Serge Poulard and Claude Scheenegans and Maxime Renard).17

Horvat and Cygra 4 group member Serge Poulard together signed a series of graphics brought together under the name Computer Triptych plus one, which, after being exhibited at the exhibition Computer Art Exhibition in Toronto in 1971, was in the same year published on the cover of the magazine Canadian Datasystems, now in the new colours facilitated by offset printing.18

Horvat did a series of four computer graphics, Conversation, 1973, in serigraphy, in an edition of 15. Conversation C1 was of a larger and horizontal format (33 x 101.5 cm). The drawing was printed with a grey line on a blue background. It shows groups of geometrical drawings of squares in permutations of distorted perspectives. A depiction of five groups of elements is mirrored horizontally, creating a harmonious composition of ten groups in all. The influence of architecture and the problems of a perspective depiction are obvious. The next three graphics, Conversation C2, C3 and C4, are smaller (33 x 32.5 cm) and show two groups of eight elements on a yellow square that serves as a background. The works were programmed by Horvat and Poulard, and processed on the CDC 1700 computer of Montreal University.

In 1974, Horvat did a larger series of computer graphics called Eratos, some of which he also reproduced in silkscreen. In addition to the main title Eratos, the works differ in their names by the letters indicating the production parameters (for example Eratos H1 bis H5L5, Eratos U H5L5, Eratos U H10L10, Eratos H bis H5L20 and so on). A work in silkscreen at the exhibition Static Computer Art Exhibit -- ACM77 in Washington in 1977 was presented as Eratos Noir, and the technique given was silkscreen printing after a drawing produced on a Verasatec plotter. All the works were line drawings from mainly horizontal and vertical lines that formed various permutations of forms that varied in their width and height. The next series of 1974 was titled in French - Ne perdez pas, mon frère, l\'espérance de vous avancer dans la vie spirituelle, or Be careful, brother, not to lose the hope of making progress in the spiritual life, a quote from one of the most popular Christian works, the Imitation of Christ by St Thomas à Kempis of 1441. It is to be found in Book 1, "Useful advice for entry into the inner life", section 22 "On human misery". The basic graphic element is made of lines that intersect at various angles multiplied in a matrix that varies in number. The whole image is a grid with permutations of elements. Here too individual works alongside the main title have letters that signify the production parameters.

In the art of the second half of the 20^th^ century opposed and contrasting aesthetic and artistic procedures unfolded at the same time and sometimes, marvellously enough, they were practised by the same people. This is shown by the work of Miljenko Horvat. His work is perceived in Croatia almost exclusively as that of a member of the Gorgona group, in the aftermath of the Gorgona exhibition of 1977.19 His computer graphics were never published or mentioned in public from the end of the 1970s and it is not surprising that they should have been forgotten.20 They were not presented in Croatia subsequently to tendencies 5 of 1973 until 2011 in Zagreb.21 Želimir Koščević observed that there was no Horvat "in the single integral review of recent photography in Croatia of 1993."22 Although exhibition and catalogue were done in a time of very marked interest in conceptual practice and its pertaining photography, Horvat evaded the attention of the curators."23 After two solo shows in Zagreb in 1961 and 1965,24 the next one was held 47 years later, in 2012, and was a selection of hand produced drawings and photo-collages.25 I would commend every reference to Horvat's work that takes into consideration his simultaneous working on a number of different aesthetic levels, and accept the viewpoint of Janka Vukmir, curator of the Zagreb exhibition of 2012:

I hope that this review of the work of Miljenko Horvat, although very modest when compared to the whole of his work, will enable a public that so far has not had many chances to see his works, and young artists also, to open up a new chapter in the understanding of the development of contemporary art during the second half of the 20^th^ century, over a broad territory, from the Zagreb of the late 50s and early 60s, via Paris and Canada, to Zagreb at the beginning of the 21^st^ century. Perhaps it will also help in the understanding of the simultaneous developments of art at a time when we were not able with the same ease as today to engage in ongoing communication and be informed about events at the other end of the world, although we were after all thanks to the work of the artist to be connected by standpoints or anti-standpoints, the main role being played, as in the case of Miljenko Horvat, by gestures, impulses, persistent work and not by theory, his works and his standpoint in the end enabling us to understand and accept, that, at the end of it all, there is nothing to understand.26

-

Darko Fritz, \"Paralelne stvarnosti -- pluralitet likovne scene u Hrvatskoj 1960-ih godina: od Novih tendencija do grupe Gorgona\", Prostor u jeziku / Književnost i kultura šezdesetih. Proceedings of papers of the 37th seminar of the Zagreb Slavic Studies School, ed. K. Mićanović, Zagreb, 2009., pp. 127--135; Darko Fritz, \"Vidljivost i ograničena vidljivost\", paper read at the symposium Moderna emancipacija -- emancipacijske moderne: simpozij u čast Matka Meštrovića, Economics Institute, Zagreb, December 5, 2013, unpublished. ↩

-

For the work of the Gorgona group, see Marija Gattin, ed. Gorgona, Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb, 2002; Ješa Denegri, Gorgona, Agroinova d.o.o., Zagreb, 2002. ↩

-

Ivan Picelj, "Za aktivnu umjetnost / Pour Un Art Actif", a, art journal, self published, Zagreb, 1962, n. p. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Marija Gattin, "Upute, Miljenko Horvat: Gorgona br. 7, 1965.", Gorgona, ed. Marija Gattin, Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb, 200, pp. 30--31. ↩

-

Museum of Fine Arts, Montreal; Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; Museum of Modern Art Haifa; Winnipeg Art Gallery, Winnipeg; Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb; MMCA Rijeka; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ottawa; McGill Universi[t]{.mark}y, Montreal, Sherbrooke and Ottawa and others. ↩

-

I am Still Alive May 14-28, 2000, Gallery PM, HDLU, curator Darko Fritz, organisation mi2. I Am Still Alive, exhibition catalogue ed.Darko Fritz, mi2, Zagreb, 2000. For the website of I Am Still Alive follow this link: https://darkofritz.net/curator/alive/index.htm, accessed 1/7/2020. ↩

-

Božo Bek (ed.), U susret Muzeju suvremene umjetnosti: 30 godina Galerije suvremene umjetnosti, exhibition catalogue, MTM / Galleries of the City of Zagreb, Zagreb,1986 (288 pp.). ↩

-

I found out that it was the same person from Marija Gattin, who told me in conversation. ↩

-

Collective shows of digital graphics in which Horvat tok part from 1971 to 1977: Computer Art Exhibition, Toronto, 1971., Exposition internationale d'art a l'ordinateur, Montreal, 1972, tendencije 5, Zagreb, 1973, Ordinateur et Creation Artistique, Pariz, 1973, Computer Art Exhibition, Toronto, 1973, International Computer Graphics, Canadian Computer Show, Toronto, 1973, Sigma 9, Contact II, Bordeaux, 1973, Interact, Edinburgh Festival, 1973, Cybernetic Artrip, Tokyo, 1974, Canadian Computer Show, London, 1974, Musée Cybernétique, Montreal, 1974, International Computer Graphics, 5th International print Biennale, Krakow, 1974, Canadian Computer Art Exhibition, Toronto, Cybern Art 74, Toronto, 1974, Art et Ordinateur, Sherbrooke, 1975, The Computer Art Exhibition, Rhinelander Gallery, New York, 1975, ICCH/2, Los Angeles, 1975, International Computer Arts Exhibition '76, Tokyo, 1976, Grafica delle arti sperimentali, Florence, 1976, Computer Graphic Art Exhibit, New York, 1976, Computer Art Exhibition -- ACM 77, Seattle, 1977, TELIC, Art Research Center, Kansas City, 1977, Static Computer Art Exhibit -- ACM77, Washington, 1977. ↩

-

Crno na bijelome, Black on white, interview occasioned by the exhibition, with Alexis Lefrançois, June 1980, translated by Tatjana Brodnjak, Miljenko Horvat, Museum of Contemporary Art -- Montreal, November 6 -- December 14, 1980. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

"Miljenko Horvat", discussion with Raymond Gervais, Parachutes, no. 5, 1976. ↩

-

Ruth Leavitt, "Miljenko Horvat", Artist And Computer, Creative Computing Press, Morristown, New Jersey / Harmony Books, New York, 1976, p. 79. A reproduction of Horvat's computer graphic Eratos of 1974 is included. ↩

-

Lucija Dujmović Horvat, Bilješke o prvim godinama u Montrealu i Miljenkovim aktivnostima, Zagreb, October 4, 2012, digital text, unpublished ↩

-

Exposition internationale d'art a l'ordinateur, Montreal, 1972. ↩

-

Bernard Levy, "Graphisme et ordinateur", Vie des arts, no. 65, 1970--1971, pp. 52--55. ↩

-

Canadian Datasystems, no. 11, December 1971. ↩

-

Gorgona, Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb, 1977. Curator: Nena Dimitrijević. ↩

-

Cf. n. 10. ↩

-

for active art - new tendencies - 50 years later - 1961-1973, Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb ↩

-

Hrvatska fotografija od tisuću devetsto pedesete do danas, Gallery of Contemporary Art, Zagreb, January 10 to February 7, 1993. Curator Davor Matičević (catalogue of exhibition). ↩

-

Želimir Koščević, "Miljenko Horvat", Kritike, predgovori, razgovori, Durieux, Zagreb, 2012, pp. 703--715. ↩

-

Galerija DARH, Zagreb, 1961 and Galerija SC, Zagreb, 1965. ↩

-

Miljenko Horvat, Imam veliki nedostatak: nemam nikakvu teoriju [I have one big lack, I don't have a theory of any kind], exhibition catalogue, Academia Moderna Gallery, Zagreb, 2012. Organisation: Institute for Contemporary Art; curator Janka Vukmir. ↩

-

Janka Vukmir, "Imam veliki nedostatak: nemam nikakvu teoriju", Miljenko Horvat, exhibition catalogue, Institute for Contemporary Art, Zagreb, 2012, p. 15. ↩